Foreign direct investment

To understand the full impact of FDI, look past the headlines

Published 22 August 2016 | 4 minutes read

For emerging markets, FDI can turbo-charge the economic development process and help countries accelerate their climb up the value chain. But while the immense dollar figures of these investments usually grab all the headlines, they don’t even begin to tell the whole story of the impact of FDI.

Scan the pages of any business publication and you’ll find example after example of eye-popping foreign direct investments (FDI) taking place in every corner of the globe.

Recent reporting by Reuters, for instance, tells us that Pfizer is investing $350 million on a plant for biotechnology drugs in Hangzhou, China. Samsung plans to invest $300 million in a data center in Hanoi, Vietnam, while Cisco reports it will invest $100 million to support India’s digital push to connect more households to the internet. The list goes on.

For emerging markets, FDI can turbo-charge the economic development process and help countries accelerate their climb up the value chain. But while the immense dollar figures of these investments usually grab all the headlines, they don’t even begin to tell the whole story.

We are now learning that the full range of FDI impacts extend far beyond the surface level of plant construction and new jobs. FDI typically brings with it a host of other less obvious benefits, which amplify the impacts of the initial investment and extend productivity enhancements deep into the host economy. FDI providers become stakeholders in the cities, towns, and provinces where they set up operations, working hand-in-hand with local communities, companies and governments to develop technological capabilities, improve management competence, and raise educational quality.

The positive impact of these FDI spillover effects ripple throughout the local economy in ways that are both enduring and transformative. A bright young manager, trained by an MNC in state of the art management practices, fulfills a lifelong dream and starts a new company. Soon, he or she is hiring from the local university and instilling world-class management techniques in the next generation of executives. A local supplier, operating with out-of-date machinery that makes it impossible to compete globally, gains access to cutting edge technologies through its partnership with an FDI provider. Soon they are not only pumping out world-class products for local consumption, they are also competing successfully in previously out of reach export markets. Universities are drawn into the mix as well, forming partnerships with FDI providers to conduct joint research and development programs that produce not only new technological breakthroughs, but also a new generation of scientists and engineers whose hard work and world-class skill sets will boost the country’s economic competitiveness for decades to come.

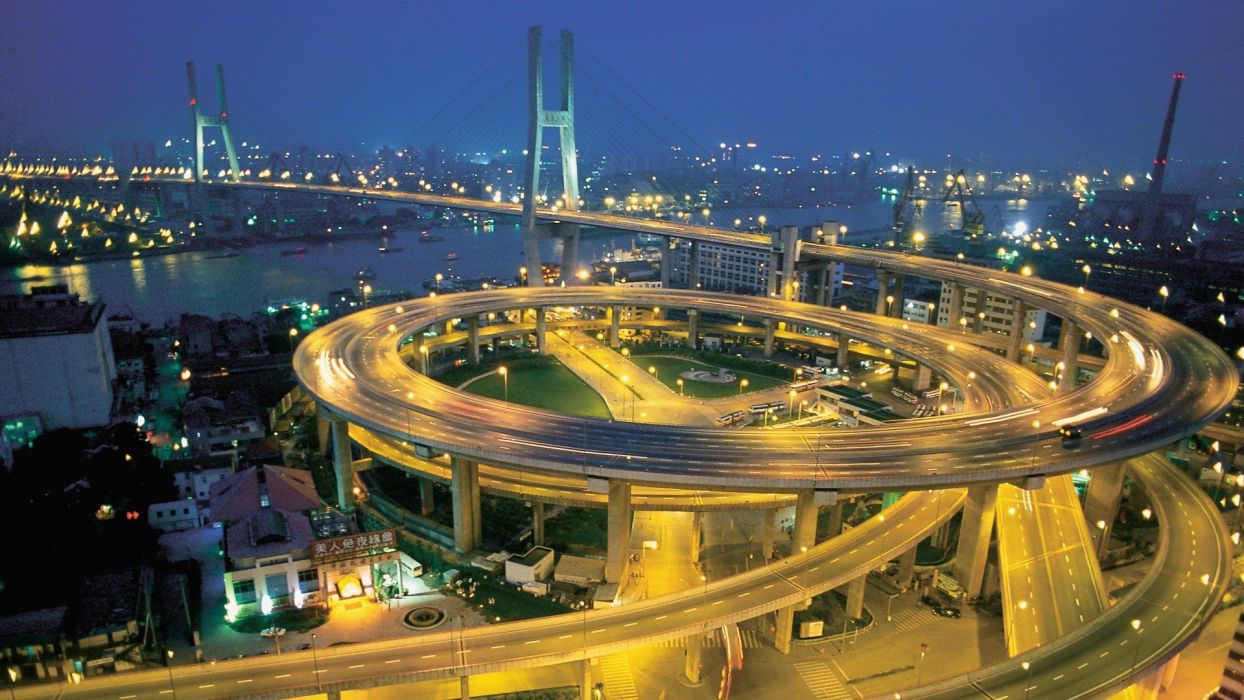

No country illustrates the transformative potential of foreign direct investment better than China, a country that was able to remake its economy in just three decades — thanks largely to precisely these types of FDI partnerships.

In a forthcoming book on FDI in China, Professor Michael Enright has been able to quantify — for the first time — the full impact of FDI on China’s remarkable economic rise. The results are striking, to put it mildly, and Professor Enright’s groundbreaking economic impact analysis is bolstered by instructive corporate case studies that tell the story behind the numbers.

Samsung provides an especially compelling illustration. While the Korean consumer electronics giant directly employs over 60,000 people in China and has cumulatively invested billions of dollars over the years, this is just the beginning of the story.

In the early days of its operations in China, the quality and sophistication of local electronic components manufacturing was simply not up to the standards Samsung required. While this initially meant importing components from Korea, Samsung embarked on a program to develop local suppliers. It ran a number of programs to provide support in the form of training, technology, and even funding – helping local companies to raise their game to global standards. Samsung also developed a supply chain management system, connecting first and second tier suppliers to reduce inventory levels and improve supply chain network efficiency.

Samsung has also made significant contributions to the development of Chinese research and development capabilities, moving significant R&D into China shortly after China’s entry into the WTO in 2001. The explicit goal was to move from a “Made in China” model to a “Created in China” model. As chronicled in Professor Enright’s book, the results have been impressive. “Samsung Electronics developed its TD-SCDMA hand phones at its Beijing Technology Center together with the Chinese hand phone maker Datang Mobile,” the book states. “Its chip making division worked with China Mobile to develop China’s 7D-SCDMA standard for 3G hand phones. At its new manufacturing complex in Xi’an, Samsung is including a research centre that will consolidate expertise from other locations in China and cooperate with local education institutions on state-of-the-art NAND flash memory chip technology.”

It would not be an overstatement to say that Samsung has essentially created an entire electronics eco–system around its China operations. The implications of this for China’s economic development have been nothing short of profound.

Of course, it should be recognized that Samsung — or any other foreign company for that matter — did not build up these substantial capabilities in China out of purely altruistic motivations. In most instances, there was a strong business rationale for undertaking these initiatives, and the investments made in developing supply chains, training management, and building research capabilities have undoubtedly helped to boost the profits earned by MNCs in China.

But this simple reality does not diminish in any way the value of these contributions. Rather, it demonstrates the true win-win potential of healthy FDI partnerships in which companies are provided a fair and reasonable opportunity to pursue profits, while host countries are able to develop technological, management, and educational capabilities that might otherwise take decades to achieve – or perhaps be out of reach altogether.

Building, maintaining, and strengthening healthy FDI partnerships such as these will continue to be key not just in China, but in other emerging markets as well. Because while the dollar value of FDI projects will usually grab all the headlines, the full implications of those investments will run deeper, wider, and longer than any headline could ever capture.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).