Published 25 October 2019

Where will UK-EU trade head after Brexit? Three years of Brexit negotiations have been about the terms of a "withdrawal agreement" which provides for a transition trade agreement. The longer-term trade arrangements between the EU and the UK are still up for negotiation.

Near and yet so far

In 2016 the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union (EU). The three years of negotiation that ensued have thus far been about the terms of a “withdrawal agreement” which provides for a transition trade agreement. The longer-term trade arrangements between the EU and the UK are still up for negotiation.

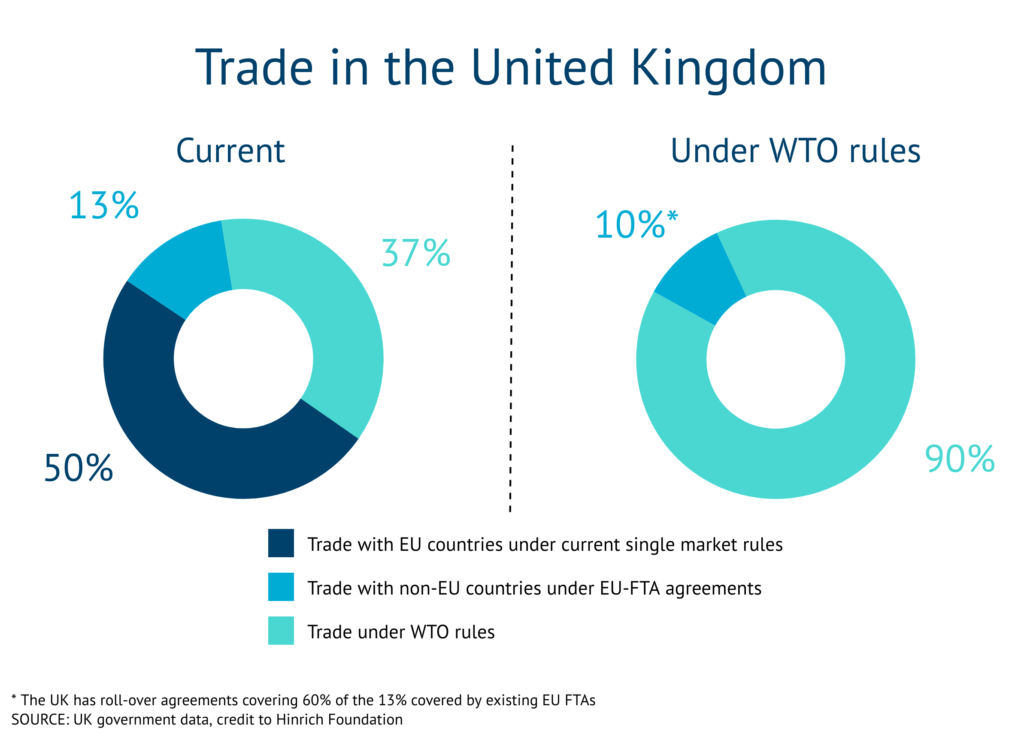

Any deal pertaining to the withdrawal agreement does not preclude a future scenario in which the UK and EU trade based on World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. This would mean that trade between the EU and the UK would migrate from being governed by the rules of the European single market and customs union to being governed by WTO rules. The proportion of UK trade taking place under WTO rules is 37 percent today. It would increase to about 90 percent.

Given the EU’s determination to protect the single market and the UK’s desire to pursue free trade agreements (FTAs) in its own right and operate outside the customs union, a WTO rules-based relationship is still a distinct possibility.

UK-EU is the second largest trade relationship in the world

The UK-EU trade relationship is large and deep: a function of 40 years of economic policy designed to integrate Europe’s economies (culminating in the single market for goods and services) combined with the geographical proximity of the two markets. As well, the EU as a customs union has meaningful tariff protection from outside competition in certain industries, notably agriculture and autos.

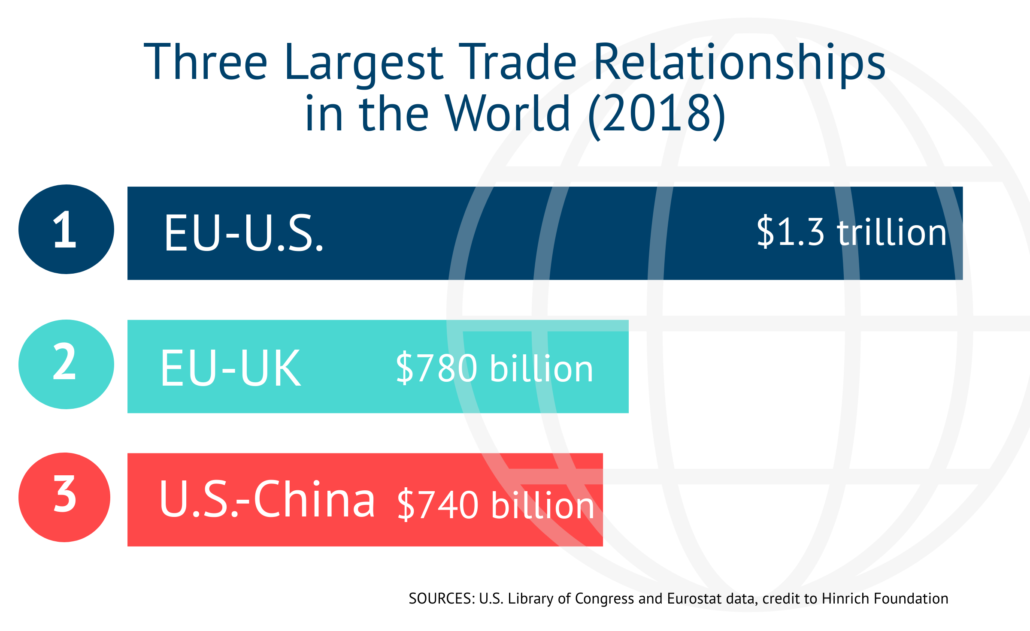

Bilateral trade between the EU and the UK was worth GBP 642 billion in 2018 (USD 780 billion at current exchange rates), making it the second largest bilateral trade relationship in the world. Therefore, the future of EU-UK trade is very important.

For context, U.S.-China bilateral trade in 2018 was USD 740 billion. EU-UK trade is about 3.1 percent of total world trade.

Trade with the EU is about 50% of UK trade overall

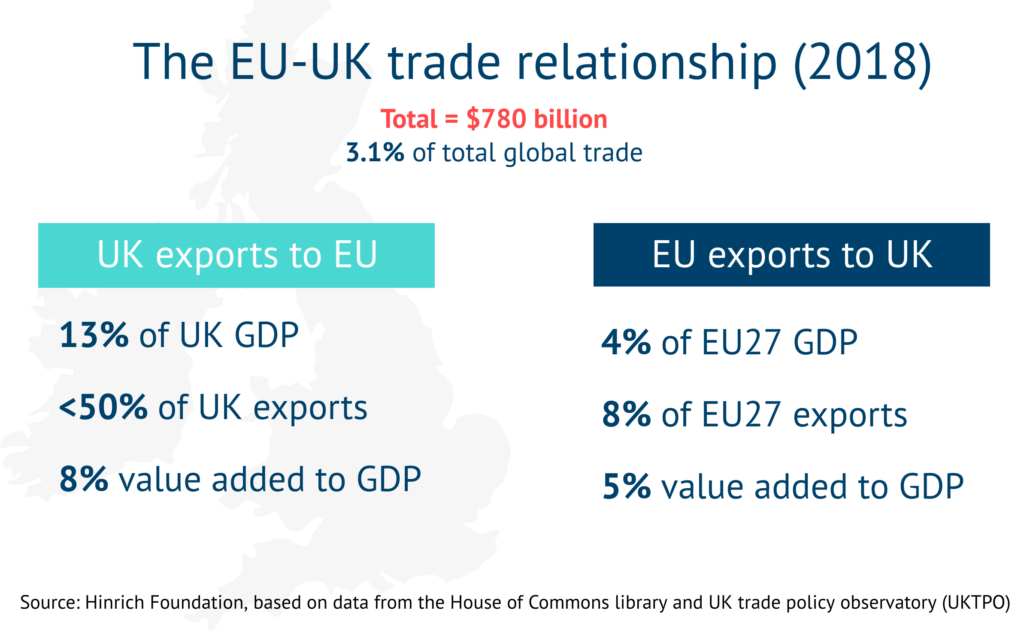

For further context, although the trade relationship is important to both parties, the UK is unique in that trade with the EU represents about 50 percent of total UK trade whereas for most EU member states, intra-EU trade accounts for the vast majority of their overall trade.

UK exports to the EU account for 45 percent of total UK exports (although this is somewhat inflated by transshipments through Rotterdam), which in turn account for about 13 percent of UK GDP and eight percent of UK value added. About 55 percent of UK imports come from the EU.

EU exports to the UK account for about eight percent of total European exports from the EU27 or about 18 percent of extra-EU exports (once the UK is outside the EU). This is equivalent to about four percent of EU27 GDP.

Check, please: The cost of a WTO-rules Brexit

From a trade perspective, the lack of a withdrawal agreement and therefore any transition period means that the UK and EU would trade on WTO rules from November 1, 2019 (or whenever it leaves), i.e., there would be a “WTO-rules Brexit”. Furthermore, FTAs between the EU and third countries would no longer apply to the UK, except where “rollover” provisions have been put in place.

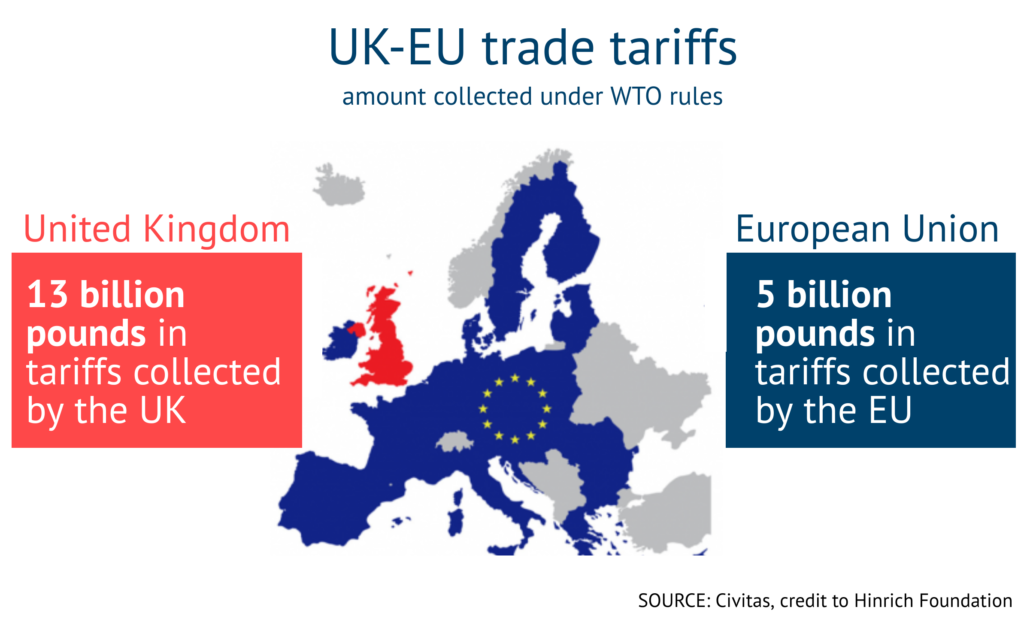

Under existing EU tariff schedules lodged with the WTO, and given current trade patterns, tariffs into the EU will be relatively low upon a no-deal Brexit. A Civitas study using 2015 data forecast a total tariff bill of GBP 18 billion, comprising GBP 13 billion on EU goods and services into the UK and GBP 5 billion on UK goods and services into the EU. This represents about three percent of total trade between the parties.

At least initially, given regulatory alignment and pre-existing business relationships, one would expect non-tariff barriers to be low too. Studies do suggest however, that there are very meaningful non-tariff barriers faced by third countries exporting to the EU and over time these could rise in the absence of an FTA.

The small size of the tariff bill and the existing regulatory alignment suggest that, although trade might suffer between the two parties, the outcome should not be disastrous at an aggregate level. The tariffs are not evenly spread, however.

About 90 percent of UK-EU trade will be tariff free under existing schedules, but in agriculture and automotive there are very meaningful levels of tariff protection in the EU. The UK has indicated that it will stick closely to the EU tariff schedule in the first instance in order to minimize disruption.

Given the relative size of the EU27 and the UK it is broadly agreed that the impact of Brexit on the UK is potentially greater than that on the EU, although that will depend somewhat on trade policies put in place post-Brexit.

The UK Government made a net contribution to EU finances of GBP 11 billion in 2018 and stands to raise GBP 13 billion from tariffs on EU imports under current rates and patterns of trade. This GBP 24 billion annual fiscal gain will provide a substantial fiscal cushion to any short-term negative impacts from trade disruption.

The impacts on trade and investment of a no-deal Brexit? It’s a moving target.

Aside from the direct fiscal consequences of Brexit, which are unambiguously positive for the UK and negative for the EU, the main channels through which the UK’s departure from the EU will impact the economies of the two parties are through trade and foreign direct investment (FDI).

A number of studies have been carried out to try to assess this impact. Those by the UK Treasury (HMT), the OECD and the IMF have received much attention as have private studies by various academics. These studies have tended to adopt the following approach:

- They use gravity models to estimate the degree to which trade and FDI has been augmented by EU membership and assume this benefit (or a portion of it) unravels; then

- They put the reduced trade and investment results into a general economic model to arrive at direct and indirect consequences for growth and productivity; then

- They present the resulting loss of economic growth as a number relative to a status quo or base line GDP outcome.

The very wide range of outcomes from these studies demonstrate the different assumptions, use of different methodologies, and the potential for bias.

For example, the HMT report used the trade augmentation for the average EU country rather than the UK itself. Other studies have tried to assess the differing impact of EU membership on trade volumes over time: when global tariffs were high the benefit of being inside the EU was greater than when global tariffs were low for example.

There are other issues too. The baseline is of course a guess: who knows what will happen to the EU27 over the next 15 years (with the UK in)? Would the UK’s fiscal contributions change? Would the UK be called upon to participate in expensive bail-outs? Furthermore, given how long the UK has been in the EU and the fact that nearly all the UK’s close neighbors are in the EU, isolating the impact of membership form other factors in the UK’s trade patterns in very challenging.

For what they are worth, these studies have concluded that UK-EU trade will suffer a decline of between 40 percent and five percent as a result of migrating from the single market and customs union to WTO rules.

Over 15 years, the studies suggest the Brexit impact on UK GDP is likely to reduce it by up to nine percent but with most outcomes clustered around minus four percent. In the worst case this might translate into about a 70 basis point lower annual growth rate than might otherwise have happened (using two percent real growth as a baseline). Most studies have results concentrated around negative four percent impact by 2030 which translates into a 28 basis point decline in annual growth.

Understandably, few studies have tried to second guess the policies that an independent UK Government might put in place post-Brexit – there are simply too many possible permutations. However, Minford et al, writing for Economists for Free Trade, have modeled the scenario in which the UK moves unilaterally to zero import tariffs and have concluded that this would boost UK GDP by four percent versus a baseline. This result is not undisputed, but it is indicative of how outcomes can change once a policy response is factored in. Similarly, studies that have assumed an EU-UK FTA produce more favorable results than those that assume WTO rules stay in place over the medium term.

Does Brexit present opportunities for more beneficial trade deals?

The UK’s interests in trade differ from those of the EU. The UK is not self-sufficient in food or energy. It is in its national interest to import food and energy at the cheapest possible prices. Alternative energy sources may lead to long term self-sufficiency in energy in the future, but the UK will always likely be a net food importer. On the other hand, the EU produces a surplus of food.

Export priorities for the UK include increasing overseas market access for its service providers and high-end manufactured products. EU exports are more dominated by manufacturing (and less by services).

These differences in trade interests create opportunities for a bespoke trade relationship that could be more beneficial for the UK than being part of an EU trade policy which attempts to balance the competing interests of the members of the bloc.

Aggregate impact of a no-deal Brexit on the UK and EU – it depends.

The conclusion that can be drawn is that if the UK leaves the EU and trades for an extended period with it on WTO terms as they currently stand, the negative consequences of Brexit could knock about 0.25 percent per year off the UK’s growth trajectory.

However, the potential to produce a positive outcome from Brexit for the UK economy exists. It lies in cutting tariffs and pursuing trade at global prices outside of the customs union thus prioritizing consumer welfare.

The fragility of the EU economy makes it vulnerable to relatively small shocks and it is to be hoped that Brexit is not the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

An EU-UK FTA, that respects the integrity of the Single Market while affording the UK the maximum freedom of action to forge an independent trade policy is most probably the optimal solution and a WTO Brexit does not preclude that happening in the future.

The original version of this article was published as “How a WTO rules Brexit would impact the EU and UK” on the Hinrich Foundation website.

Download and share our TradeVistas “Road to Brexit” timeline here.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).