Sustainable trade

Where To Be Or Not To Be: How Companies Answer That Question

Published 05 January 2017

Shortly after his election in November, President-elect Donald Trump announced he made good on one of the promises of his campaign - to save jobs at a Carrier plant in Indiana that had been slated to move to Mexico. Trump's announcement was great news for the Carrier employees who are keeping their jobs but it also perpetuates some misconceptions about where companies choose to locate and why and what it takes to bring back jobs to the United States.

Shortly after his election in November, President-elect Donald Trump announced he made good on one of the promises of his campaign – to save jobs at a Carrier plant in Indiana that had been slated to move to Mexico. The deal is expected to preserve about 1,000 jobs for the near future. In return, the company will get about $7 million in tax incentives from the state.

Trump’s announcement was great news for the Carrier employees who are keeping their jobs. It also made for great optics for the President-elect. But it also perpetuates some misconceptions about where companies choose to locate and why and what it takes to bring back jobs to the United States:

Labor costs aren’t all that matters.

Many people may believe that companies are locked in a “race to the bottom” for the cheapest labor they can find and that they will locate production where wages are lowest.

Wages do make up a large share of companies’ costs, but it’s also only one variable companies consider in deciding where to locate. High-tech manufacturers, for example, may prefer an educated, high-skilled (and high paid) workforce conversant with the technology necessary to make complex, high-quality products. An increasing share of U.S. manufacturing falls into this category, and many companies in fact report a “skills gap” among the workers they need to fill available jobs.

The ability to protect intellectual property may also be important. For example, advanced manufacturers that rely on proprietary technologies may prefer a country with strong intellectual property protections and rule of law, in addition to a favorable tax and regulatory environment. Some companies may also want their production facilities closer to where they conduct their research and development.

There are also a few factors that companies cannot control in choosing where to site their facilities, such as where their customers are and where their suppliers are. If the costs of transporting or distributing a product are high – such as for heavy machinery – companies may want to be as close to their customers and suppliers as possible to cut down costs.

In fact, companies have come to realize that offshoring has some major disadvantages because of the distances often involved. A 2011 survey of manufacturers by Accenture, for example, found that when companies put production facilities too far away from their customers, they “hurt their ability to meet their customers’ expectations across a wide spectrum of areas, such as being able to rapidly meet increasing customer desires for unique products, continuing to maintain rapid delivery/ response times, as well as maintaining low inventories and competitive total costs.”

Shipping goods long distances can mean supply chain disruptions for a number of reasons, including natural disasters such as tsunamis and earthquakes. Accenture’s study found that nearly half of manufacturers complained that offshoring resulted in poorer quality goods and problems meeting deadlines for delivery.

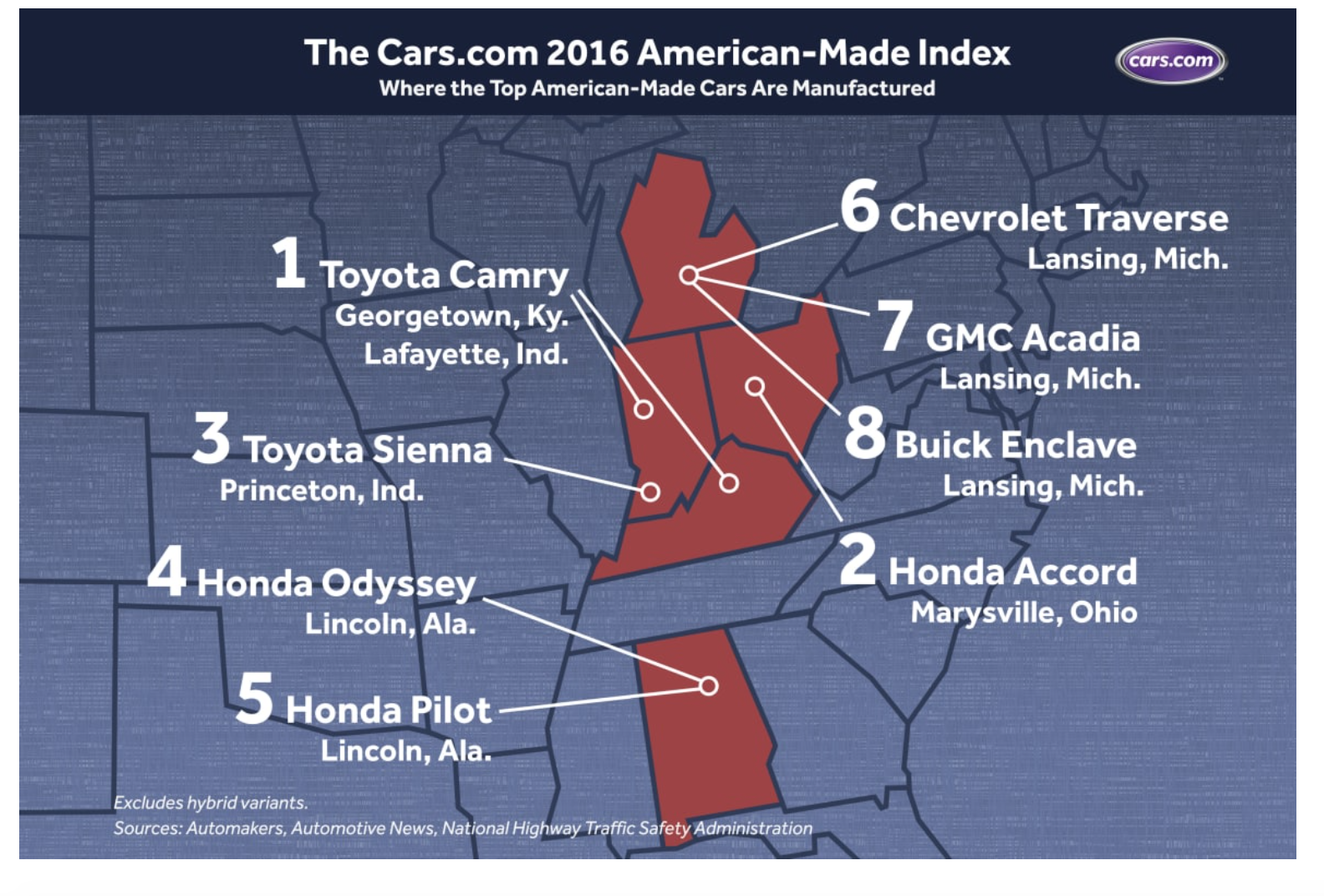

This desire to be closer to customers is one reason why so many foreign car manufacturers make their cars in America. It’s cheaper to build a car in Ohio and sell it to someone in California than it is to build a car in Japan and ship it in a container halfway around the world. According to the 2016 Cars.com American-Made Index, the top 5 “American” cars – cars assembled in the United States with a high percentage of domestic parts and that are sold mostly to American consumers – are by Japanese automakers. (These foreign companies are technically “offshoring” to America.)

The #1 ranked Toyota Camry, for example, is made is Georgetown, Kentucky, and Lafayette, Indiana, while the #2 ranked Honda Accord is made in Marysville, Ohio. According to Cars.com, “U.S. vehicle production from Japan-based automakers has climbed from 2.3 million cars in 1995 to more than 3.8 million in 2014.”

A 2011 study by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute concluded that siting decisions ultimately depend on “low-cost supply-chain effectiveness” versus simply “low-wage production and sourcing.” The “winning combination,” the report found “will be one that can provide the ‘best’ total value chain—combining innovation, production, sales, and service for the final customers.”

U.S. companies are “reshoring” jobs on their own.

A significant number of American companies have decided – without the benefit of Trump’s intervention – that the place where they can best find this “winning combination” is in the United States.

The nonprofit Reshoring Initiative calculates that U.S. companies have brought back as many as 256,000 manufacturing jobs through “reshoring” jobs that were once overseas. The initiative has collected more than 400 case studies of companies moving jobs back to the United States. These companies include Caterpillar, which announced in 2015 that it was moving the production of its vocational trucks from a plant in Escobedo, Mexico, to Victoria, Texas, thereby creating 200 new jobs. The list also includes companies such as Ace Clearwater, which produces welded assemblies for the aerospace and energy sectors. According to Ace’s case study, the company moved jobs from Hungary and China to Torrance, California, because of quality control issues and the willingness of its customers to pay more for higher-quality products.

It takes more than tax breaks to keep a company from moving.

In addition to offering Carrier the “carrot” of a $7 million tax break to keep jobs in Indiana, Trump also brandished the stick of penalties for companies that move jobs offshore. Controversially, he threatened to impose tariffs of 35 percent on products made overseas and sold back into the United States.

Unfortunately, this combination of company-specific dealmaking and invective is unlikely to do much more than produce short-term results. One-time tax incentives can’t change the long-term calculus for companies deciding where to put their factories. Even in the case of Carrier, despite its deal with Trump, the company reportedly plans to close another facility in Indiana, which will mean the loss of 700 jobs to Mexico.

The right way for countries to attract investment and jobs is to provide all of the ingredients that companies find attractive: a fair tax structure without undue complexity; an evenhanded regulatory environment that provides certainty; adequate intellectual property protections; an honest and efficient government free of corruption; a healthy consumer class with rising incomes; and a skilled, entrepreneurial workforce.

In short, a country that want companies to invest in it must first invest in itself.

Additional Resources:

Manufacturing’s Secret Shift: Gaining Competitive Advantage by Getting Closer to the Customer, Accenture

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).