Sustainable trade

How America Keeps on Trucking

Published 02 March 2017

Driverless trucks will someday revolutionize shipping, with the potential to lower costs and improve safety. But what will happen to trucking jobs?

Driverless trucks will someday revolutionize shipping, with the potential to lower costs and improve safety. But what will happen to trucking jobs?

On October 20, 2016, a shipment of 50,000 cans of Budweiser beer arrived in Colorado Springs, Colorado, after traveling 120 miles across the state on I-25 from the Anheuser-Busch brewery in Fort Collins.

This was no ordinary shipment: the beer arrived by driverless truck.

Otto, the truck’s manufacturer, called this journey “the world’s first shipment by driverless truck” (you can watch a video here). And it certainly won’t be the last. Driverless trucks are poised to revolutionize the way that food (and beer) arrives at your local grocery store and merchandise arrives at your local mall.

It could also happen sooner than you think. The MIT Technology Review predicts in its March/April 2017 issue that self-driving trucks could become regular fixtures on America’s highways in as little as 5 to 10 years.

Proponents of these technologies say that driverless trucks can save fuel and reduce the number of fatalities on America’s roads caused by human error, such as driver fatigue. According to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, large trucks were involved in nearly 4,000 fatal crashes in 2014. An April 2016 report by the consulting firm Roland Berger argues that self-driving technologies could eventually reduce the accident rate to less than one-fifth of its current level. And because driverless trucks don’t sleep, goods can move across the country in less time and at lower cost.

Accelerating the deployment of self-driving trucks is the enormous amount of investment pouring in to this technology. In November 2016, Ohio Gov. John Kasich announced a plan to invest $15 million to build the nation’s first “smart road” – a 35-mile corridor in central Ohio that Kasich hopes will become a “proving ground” for driverless and semi-automated trucking. In August 2016, ride-sharing company Uber bought driverless truck manufacturer Otto, then less than one year old, for a reported $680 million.

Other parts of the world are embracing driverless technologies as well. In April 2016, convoys of semi-automated trucks made their first cross-border European sojourn as part of the 2016 “European Truck Platooning Challenge,” sponsored by the government of The Netherlands. Under this approach, two to three wirelessly linked trucks travel in tight formation to reduce drag and improve fuel economy, with the lead truck (driven with the help of a human) setting the route and the speed. In January 2017, the government of Singapore began testing a similar truck platooning system, with the help of automakers Scania and Toyota.

According to the American Trucking Association (ATA), 70 percent of America’s freight tonnage travels by truck, making trucking a vital part of the infrastructure that supports the international and intra-national flow of trade. In 2015, says the ATA, trucking was a $726 billion industry in the United States, with more than 3.6 million trucks responsible for moving more than 10 billion tons of freight across the country. The grapes from Chile and the apples from Washington State that appear in the produce section of the grocery store likely arrived by truck, as did the flat screen TVs at your neighborhood Best Buy, the pants you just bought at the Gap and the cars at your local dealership.

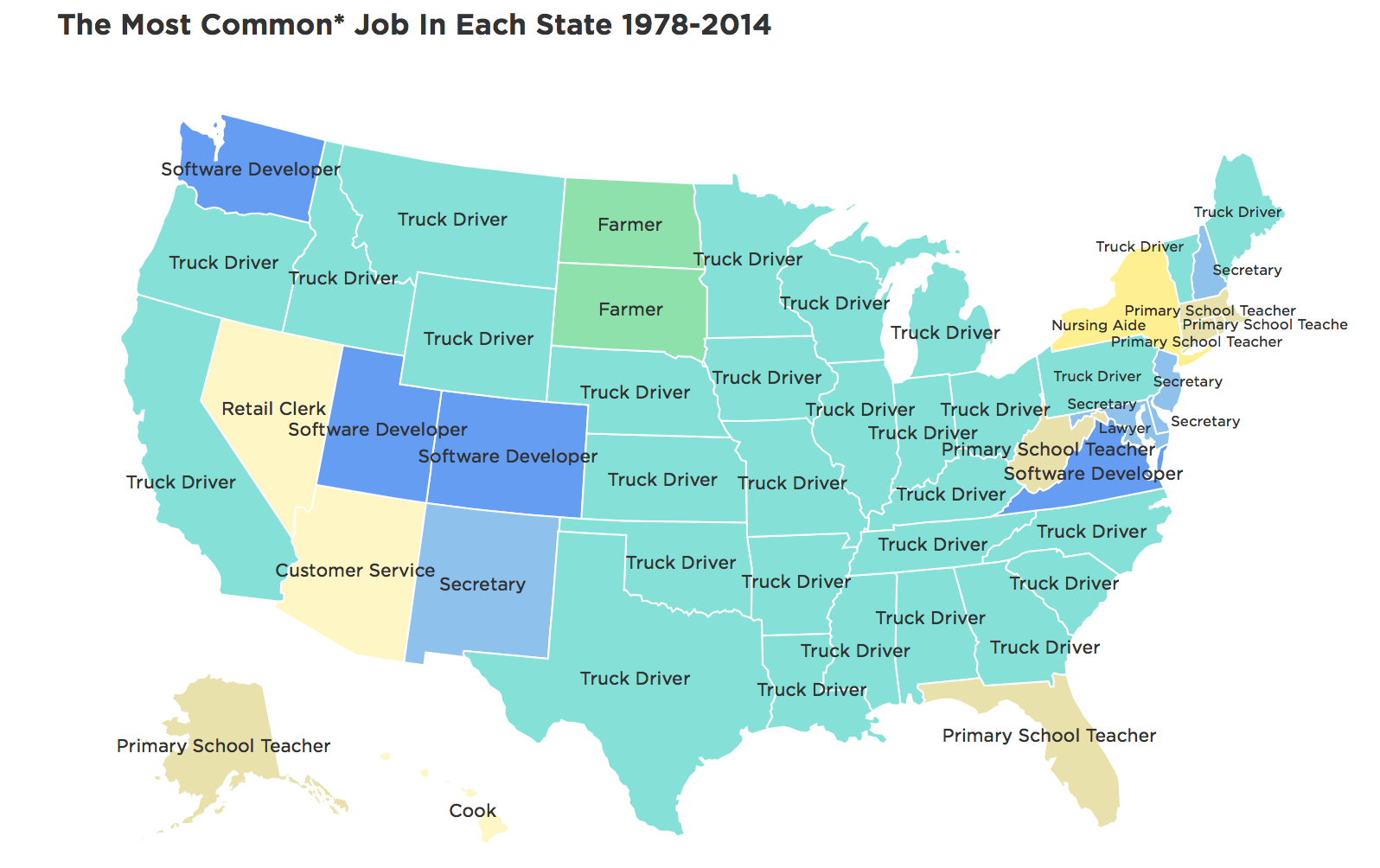

The vast amount of freight that moves by truck also means that millions of American jobs rely on the trucking industry – jobs that could disappear when driverless trucks hit the road. In 2014, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 1.8 million people made their living driving heavy trucks and tractor-trailers. The numbers are even greater if you include all workers who drive and deliver goods for a living. In fact, in 28 states, driving a truck (including smaller delivery trucks) employs more people than any other occupation.

Source: NPR

Moreover, driving a truck – which paid a median of $40,260 in 2015 – is one of the few solidly middle-class jobs left for people without a college degree. According to BLS, the average educational credentials for a truck driver is a high school diploma plus a commercial driver’s license. Driving a truck is also one of the few trade-dependent jobs that both cannot be off shored and thrives with the growth of trade. BLS in fact predicts that the number of truck driving jobs could grow by another 100,000 between 2014 and 2024 – given the status quo.

Driving a truck is one of the few trade-dependent jobs that both cannot be off shored and thrives with the growth of trade.

The advent of driverless trucks, however, will mean not only fewer truck drivers but a shift in what “driving” a truck means. Because of the complex software involved, operators of driverless trucks will likely be more like IT workers than drivers. For example, Starsky Robotics, another driverless truck start-up that aims to compete with Otto, says it plans to keep humans very much a part of its business model. But as The Drive reports, the company also envisions moving “drivers” to a central “drone-control facility” where one worker can monitor many trucks.

A shift like this would be similar to what’s happened in American manufacturing. As U.S. manufacturing has become more technologically advanced, with robots doing the repetitive assembly work once assigned to humans, factory workers must now be better educated, highly skilled and conversant with technology. Even as U.S. manufacturing is enjoying a renaissance and is more productive than ever, the sector employs fewer people in total and is not the gateway to middle-class opportunity for lower-skilled workers as it was half a century ago.

While driverless trucks could ultimately prove a boon to consumers, companies and motorists, the disruption caused by this technology could have a real and severe human toll – along with attendant political and social consequences.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).