Sustainable trade

Trade Agreements Take a Back Seat in the Great International Tax Race

Published 03 November 2017

The U.S. Congress is set to consider the first major reform of the U.S. tax code in decades. The proposed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act released on November 2 by House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) and House Ways and Means Committee Republican Members features significant changes to the way U.S. corporations are taxed and carries implications for how they compete around the world.

The U.S. Congress is set to consider the first major reform of the U.S. tax code in decades. The proposed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act released on November 2 by House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) and House Ways and Means Committee Republican Members features significant changes to the way U.S. corporations are taxed and carries implications for how they compete around the world.

Everyone Likes a Discount

Retail stores are constantly offering some percentage off your purchase, or incentives like free shipping to close the deal with you. American consumers almost never pay “full price” because they are conditioned to look for the best offer and save money. Companies are no different. If they can improve their bottom line by saving money to reinvest, hire more workers, or provide a better return to shareholders, they’ll do it. Governments around the world – competitors of the U.S. Government – offer “discounts” in the form of better tax policies to entice companies to earn money in their countries, build offices or plants, perform R&D or otherwise invest in assets in their countries.

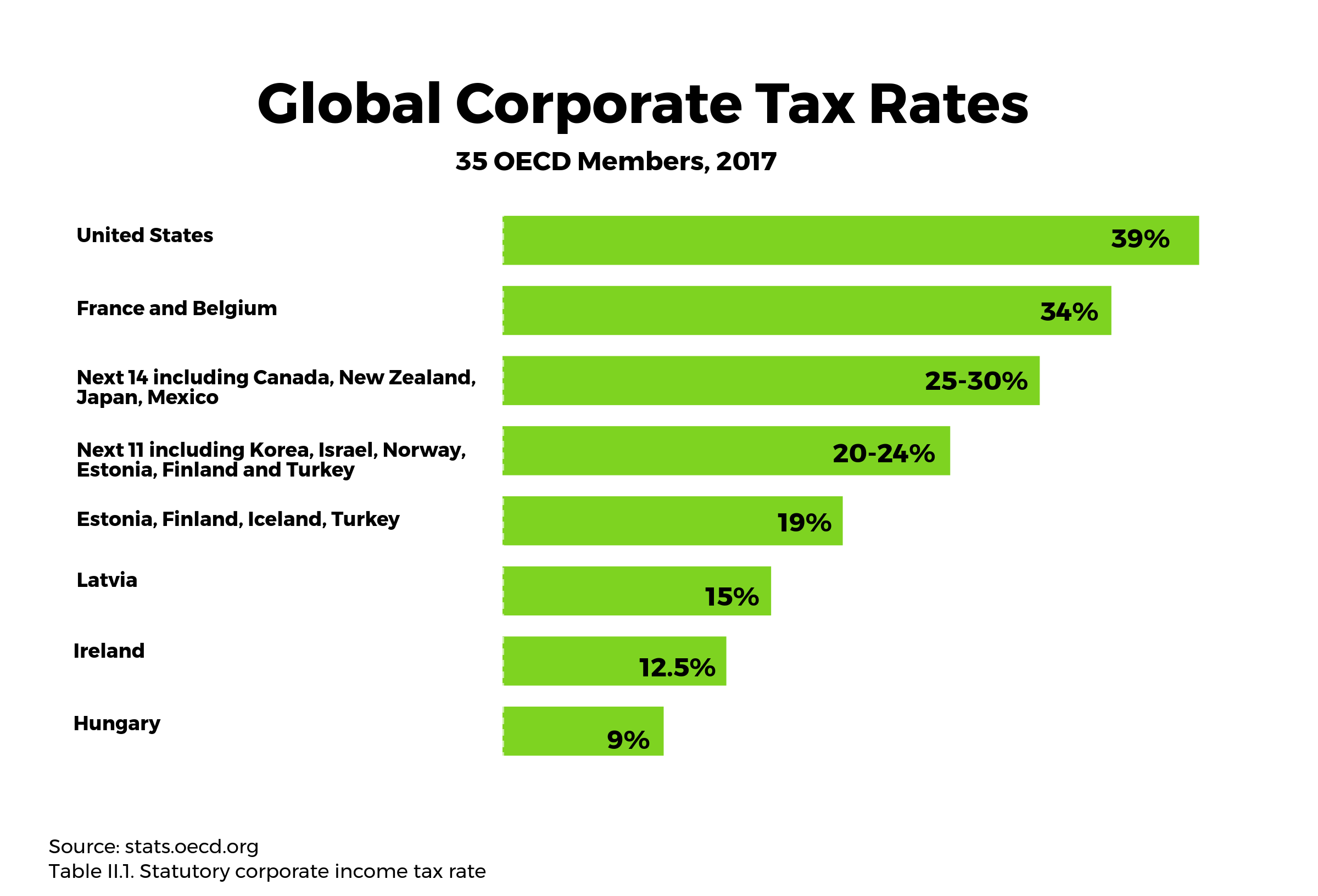

The U.S. Government behaves as if it is not in a competition for business. Not only does the United States have the highest statutory corporate tax rate, we are one of the last major economies that still taxes worldwide corporate earnings. Nearly all industrial economies have shifted to a territorial tax system that largely exempts corporate earnings already taxed in the country where they are generated. Foreign-headquartered firms often enjoy a major tax advantage over U.S.-headquartered firms, especially when they compete outside their home markets.

Taxing Decisions

American multinationals make products for, and offer their services to, customers all over the world. With every sale, they seek to earn profit for their employees, owners, and shareholders. How they are taxed drives major decisions on where to put up factories, which corporate entities will sell to their own affiliates, where R&D will take place, and how much profit earned overseas will return to a U.S.-headquartered company’s business in the United States.

Some American firms, many of which have a more than 100-year history, have made the tough, tax-driven choice to “invert” by moving their headquarters to a low-tax country. When these companies move, they may leave substantial operations in the United States, but they abandon their American legacy plus many well-paying, high-level corporate jobs. Corporate tax reform could reduce or eliminate the incentives for inversion. The current proposal would go a step further to penalize American companies that move their headquarters with a new tax.

Two Big Negatives if You’re Bargain Hunting

A big price tag: At 38.9 percent, the United States has the highest combined (federal and state) corporate tax rate of any major economy. The majority of our competitors are below 30 percent. In recent years, Japan reduced its corporate rate by 8.5 points and the United Kingdom dropped its rate by 10 points.

The big statutory price tag is why American multinationals develop tax strategies to reduce their tax burden through credits and exemptions. They do so well finding ways to avoid the 38.9 percent, the average “effective” tax rate paid by U.S. multinationals to the Federal Government is around 19-20 percent.

The fine print: 29 out of 35 OECD countries (advanced developed economies) have a territorial tax system under which companies pay corporate taxes once in the country in which their profits are earned. Their home country generally exempts those profits from being taxed again. The U.S. system taxes corporate profits earned everywhere. So, if a U.S. multinational earns money taxed at a lower rate overseas, they’ll be asked to pay the difference to the U.S. Government.

Let’s say you are Ohio-headquartered Procter & Gamble (P&G) competing against Dutch company Unilever for sales of consumer products in Canada. Unilever will pay tax at Canada’s rate of 26.7 percent. P&G will pay the Canadian rate and then be taxed another 12.2 percent by the U.S. Government to reach the U.S. rate of 38.9 percent (average state tax included) — if and when they return the profits earned in Canada back to the United States.

Boatloads of Cash

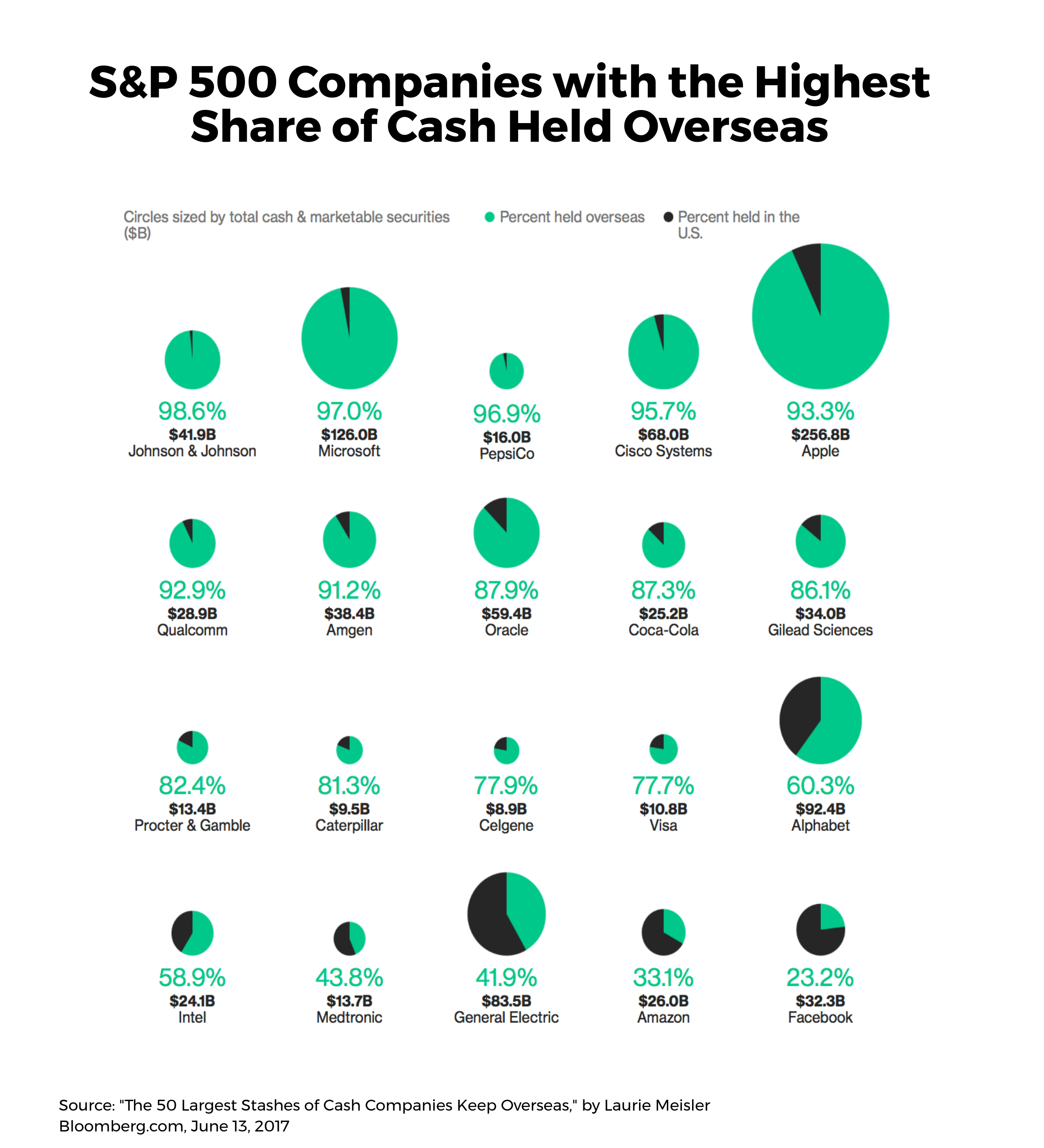

One of the most prevalent ways to minimize this problem is to defer taxes, sometimes indefinitely. Taxes on profits earned by U.S. multinationals overseas don’t have to be paid until they are repatriated or brought back to the United States. While deferral (including treatment of capital gains or individual retirement plans) has been a part of the tax code since its inception, the scale of deferral can distort decision-making.

American companies are holding an estimated $2.6 trillion overseas (equivalent to nearly 14 percent of U.S. GDP). Apple holds more than 93 percent of its cash abroad. Microsoft and Alphabet are sitting on $126 billion and $92.4 billion in cash outside the United States, respectively. The opportunity to avoid the 38.9 percent corporate tax incentivizes is not just to earn more money overseas, but to leave it or invest it there. They are likely to invest more than they would choose to in those countries absent the tax differences.

Would Corporate Tax Reform Be a Windfall – and For Whom?

Surrounding the debate over corporate tax reform is the criticism that corporate tax reform only benefits the one percent of American firms that are multinational. But consider that the one percent of U.S. multinationals generates more than 19 percent of American jobs and accounts for nearly three-quarters of R&D spending. They also generate the lion’s share of U.S. merchandise exports.

Even if the corporate tax rate is significantly reduced (the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would lower it to 20 percent) and the system shifted to a territorial one, multinational companies could still game the system by, for example, lending money from a low-tax subsidiary to the U.S. parent or by ensuring that highly-mobile assets such as royalties are taxed in lower rate tax jurisdictions, both of which reduce U.S. tax revenues. Other countries with territorial systems have closed these loopholes by taxing “passive” income such as interest or royalties while exempting “active” income from manufacturing, an approach the U.S. tech giants wouldn’t favor.

Tax Policy is at the Core of Competitiveness

Corporate tax reform is being considered seriously in Washington because there appears to be general agreement our current system is uncompetitive. Even though corporate income tax is not as large a source of federal revenue as individual income taxes and payroll taxes, our high corporate tax dampens investment in the United States — investments in technologies and people – that could boost our productivity and secure higher returns on innovation. Improved tax policies would attract companies to locate their multinational headquarters in the United States and not leave for greener tax pastures.

Corporate tax reform is therefore seen as a way to increase economic growth without suffering a significant loss in federal revenue. But, it’s complicated and there are politics at play so the timing, scope, and nature of corporate tax reform is yet uncertain. The one thing that is certain: no matter the kind of improvements to the business environment they may offer, trade agreements will take a back seat to tax policies in the global race to attract business.

Read More:

Find the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act bill, a summary, and FAQs on the website of the House Ways and Means Committee

OECD.Stat Statutory Corporate Income Tax Comparative Tables

2017 International Tax Competitiveness Index by the Tax Foundation

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).