Published 11 October 2018

American cheesemakers are having a harder time finding an outlet for production through exports. In reaction to US steel tariffs, its trading partners have raised their tariffs on cheese.

Blessed are the cheesemakers

The world loves cheese. From sharp Cheddar to smooth Camembert, pungent Gorgonzola to smoky Gouda, there’s a cheese to suit everyone’s taste. If we enjoy the variety so much, why does this beloved dairy product take center stage in so many international trade policy disputes and negotiations? Cue Monty Python’s Life of Brian when listeners at the back of the crowd have trouble hearing the Sermon on the Mount:

“What was that?”

“I think it was, ‘Blessed are the cheesemakers’!”

“What’s so special about the cheesemakers?”

“Well, obviously it’s not meant to be taken literally. It refers to any manufacturer of dairy products…”

Is it possible to have too much cheese?

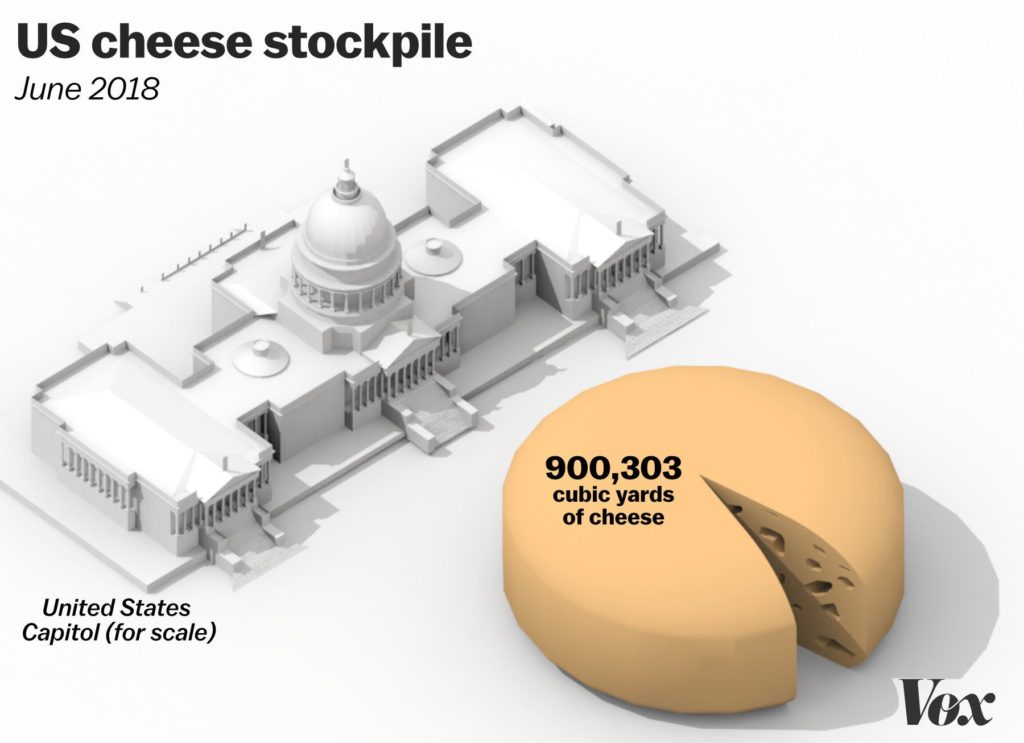

Demand for dairy has declined as more consumers seek out plant-based milk substitutes like almond or coconut. To minimize losses, the overflow of dairy can be processed and more easily stored as cheese to increase its shelf-life. The shift has caused a reported 1.39 billion pound surplus of cheese in the US market, 6 percent larger than the surplus in 2017 and 16 percent larger than the cheese surplus in 2016, which USDA reported was the highest level in 30 years.

The cheese glut is why the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced in May that it would buy up US$20 million worth or 11 million pounds of excess stock from private inventories. Section 32 of the Agriculture Act of 1935 authorizes USDA to purchase surplus food for the benefit of food banks and families that participate in nutrition assistance programs.

Lactose intolerant

The industry is having a harder time finding an outlet for production through exports. China, Canada, and Mexico are three of the most important destinations for US cheese. But in reaction to US steel tariffs, Mexico, which buys about a quarter of US cheese products, Canada, China, and the EU have all raised their tariffs on cheese, offering a double whammy for dairy producers.

Getting caught in the crosshairs isn’t new for cheesemakers. It’s a sacred cow for many countries (pardon the pun) and therefore a popular pain point to exploit in trade disputes. In 2009, George W. Bush raised tariffs on French-produced Roquefort to 300 percent after the European Union banned imports of US hormone-treated beef. And cheese has long been a common weapon in many other disputes, due to the strength of dairy industries across the globe.

Free trade full of holes

Countries use a variety of means to limit imports of foreign cheese. Like many other countries, the United States has an extremely complex tariff schedule for cheese with over 150 separate entries for types of cheese and cheese products. These range from single tariff lines for cheeses such as Roquefort or Stilton, to multiple lines with different tariffs depending on whether a cheese is in its “original loaf” or not, or suitable for grating or not, which could mean the difference between a 15 percent or 20 percent tariff.

Not only are the tariffs on cheese so varied, they are also unusually high compared to many other products. The United States is a low-tariff country with an average of 1.6 percent across all products. But US tariffs on cheese average 17 percent and regularly reach as high as 20 percent or US$2.269 per kg. In the EU, home to powerful dairy industries in France and Italy among others, the average tariff is 34 percent.

Beyond tariffs, cheese exports must comply with food safety standards, certifications, and labelling requirements, and limitations around naming for geographic areas. For a product so well-loved and ubiquitous in cuisine around the world, cheese is the perfect example of the remaining holes in free trade policies.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).