Published 29 March 2018

For many years now, the US Government has implemented a sugar program that ensures sugar producers and refiners get a minimum price for American-grown sugar. It's a hidden tax paid for by Peep-lovers everywhere.

Hidden tax on Peeps

Americans spend more on candy over the Easter holiday than on Halloween. The National Retail Federation projects Americans will spend US$2.7 billion on Easter candy this year to fill our baskets with chocolate bunnies, cream-filled eggs, and of course, those affable marshmallow Peeps.

Peeps’ parent company, Just Born (named for founder Sam Born), continues to hatch new flavors such as Pancakes & Syrup. This holiday, Just Born released “mystery flavors” available at a handful of select retailers like Walmart. All told, WalletHub thinks Americans will consume more than 1.5 billion Peeps this Easter. The iconic chicks are even finding their way into craft beer: Fort Worth’s The Collective Brewing Project developed a sour ale beer brewed with Peeps to pair with Easter ham.

The brightly colored sugar crystals adorning Peeps are an obvious reminder of an American penchant for the sweet stuff, but sugar is a key ingredient in a lot of what we eat from soup to cereal to frozen foods, canned fruits and vegetables, and breads. For many years now, the US Government has implemented a sugar program that ensures sugar producers and refiners get a minimum price for American-grown sugar. It’s a hidden tax paid for by Peep-lovers everywhere.

Price guarantees for producers and processors

The sugar program has roots as far back as 1789. What began with tariffs expanding through subsequent legislation to include government supports and quantitative restrictions on imports. The current program enshrined in the Agricultural Act of 2014 has roots in the 1981 farm bill. It is designed to provide a price guarantee to producers of sugar beets and sugarcane growers. Processors of both crops are eligible for government loans that can be secured and even repaid with sugar in some circumstances.

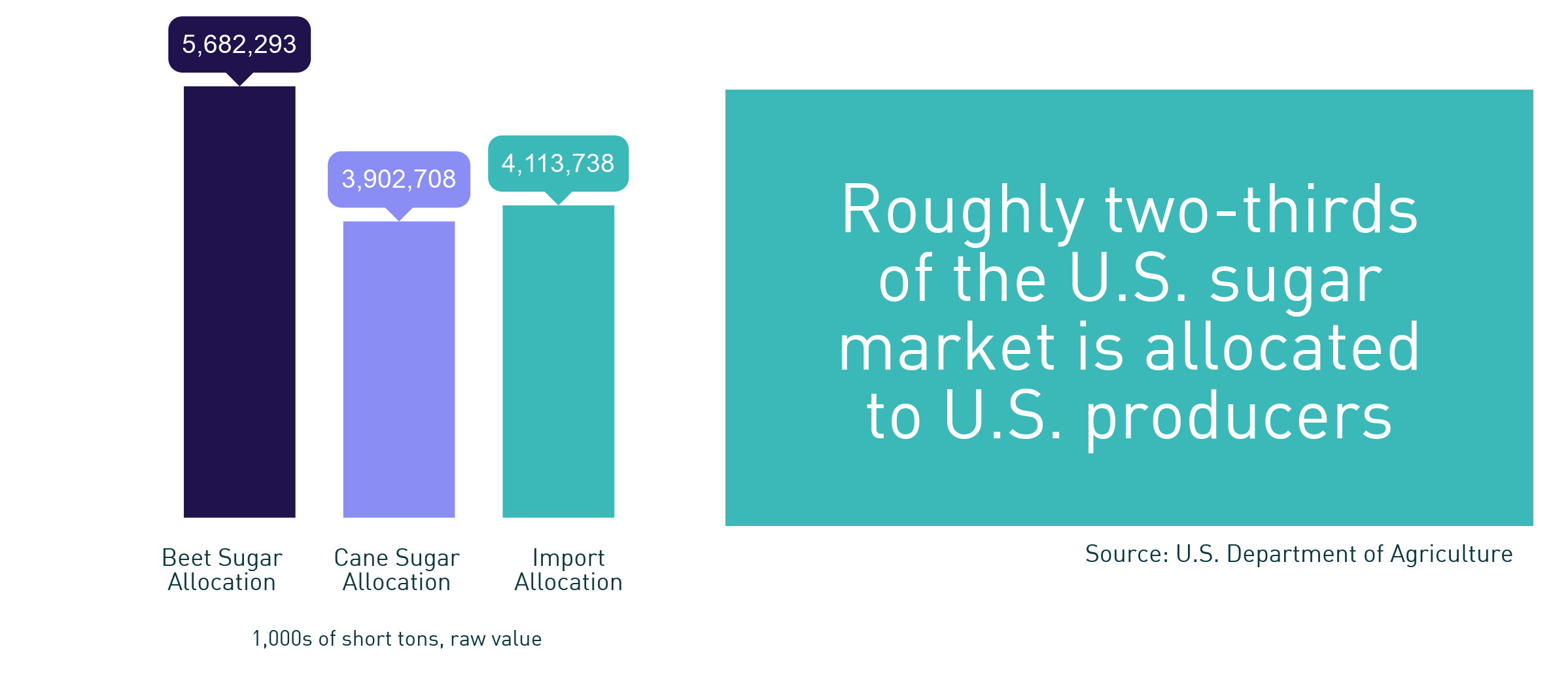

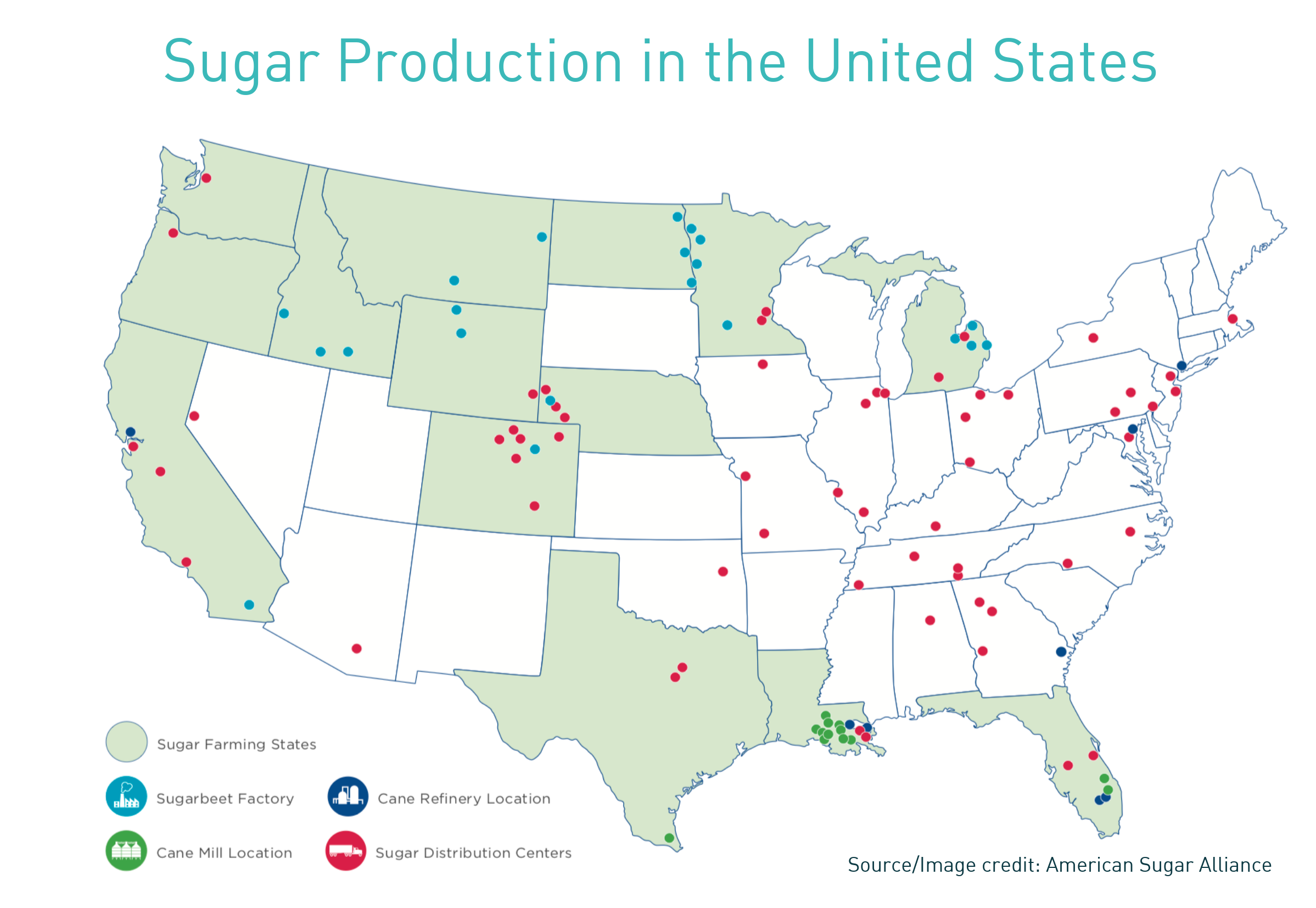

To manage the price of sugar sold in the United States, the US Department of Agriculture limits and allocates the amount of domestically produced beet and cane sugar that processors are permitted to sell each year. But US producers do not grow and harvest enough to supply the amount of sugar demanded by American food and energy producers and to supply all the bags on your grocery shelf, so we must also import some amount of sugar to meet total demand.

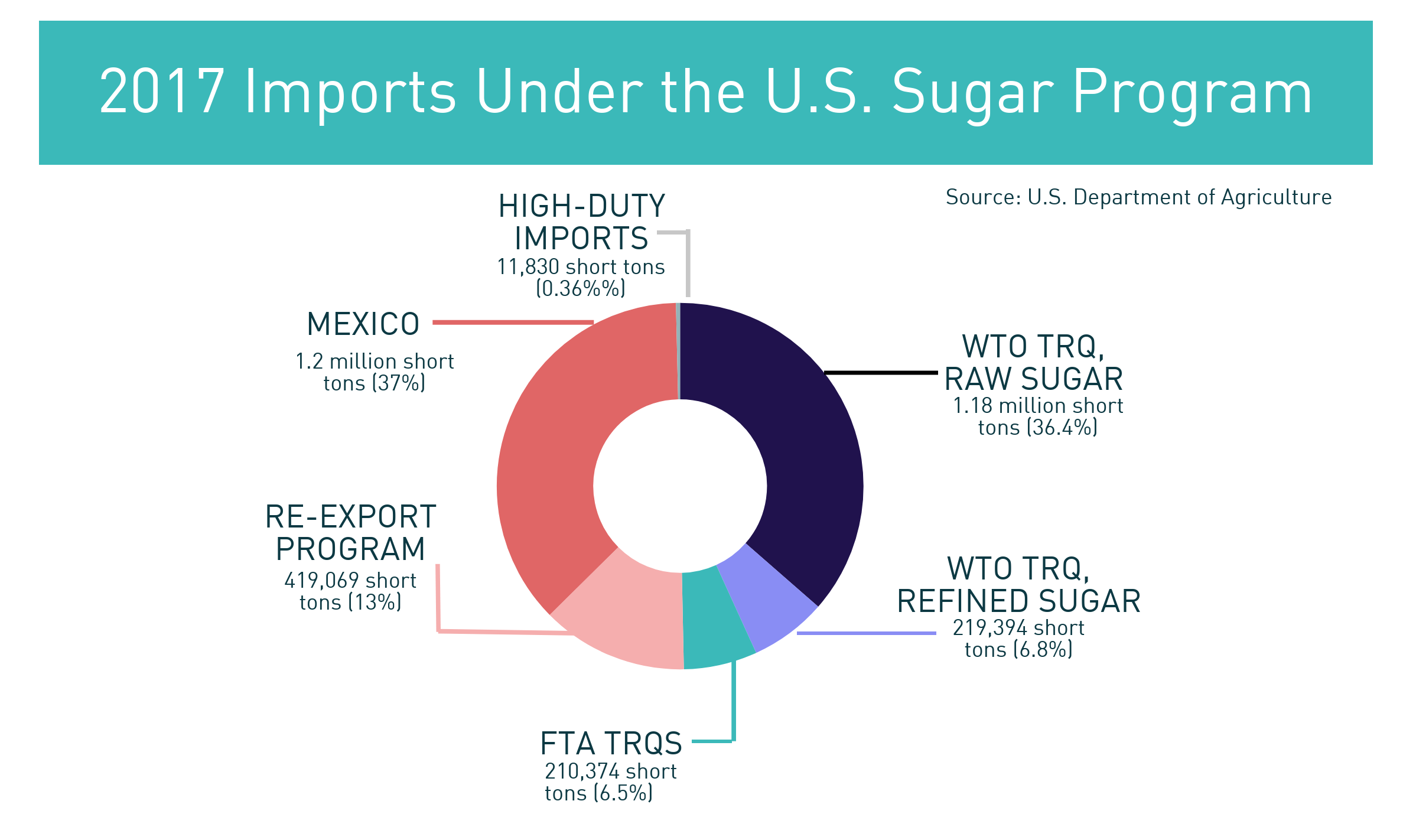

Here again, the US Department of Agriculture makes its best guess each year about how much sugar may be imported. It’s a balancing act: the United States must meet its existing international trade obligations to WTO members and free trade agreement partners, while also ensuring the market price in the United States does not fall below a guaranteed support level under the US sugar program. Allow “too much” and the market price falls below the government guaranteed price.

Who can import?

According to a 2016 Congressional Research Service report, sugar imports from fiscal year 2013 to fiscal year 2015 accounted for 30 percent of the sugar used in food and beverages in the United States. When the program was initiated, the United States agreed it would grant annual quotas to 40 countries specifying how much sugar they could export to the United States (in total 1.256 million tons of mostly raw sugar). The amount of the quotas was based on trade in sugar from 1975-1981 and have remained unchanged since. Above these quotas, a prohibitively steep tariff is applied. Additional, smaller quotas have been granted to the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Peru, Colombia, and Panama as part of subsequent free trade agreement commitments.

In 2008, Mexico was accorded duty-free, quota-free access to the US market under NAFTA (a commitment that came due after a fourteen year adjustment period), enabling Mexican producers to become the single largest group of importers to the US market. Over the 2013-2015 fiscal years, imports from Mexico comprised 55 percent of sugar imports on average. In 2014, however, the Department of Commerce concluded a set of investigations finding that Mexican sugar producers had benefited from subsidies and were selling sugar in the US market at below fair market value. The conclusion spurred consultations with the Mexican Government to avoid significant new duties applied to sugar imports from Mexico. Mexico agreed to restrict the amount its producers can export each year to the United States, and agreed to a floor price, thereby relinquishing its rights under NAFTA to free access and subjecting its exports to managed trade.

Criticism of the program

Among the more vocal critics of the sugar program are industry groups representing food and beverage companies that use sugar. They argue that the price for sugar in the United States is two to three times higher than the world price for sugar, driving up the cost of a key ingredient – a cost passed through the customer. Drive up the cost too much, or introduce too much uncertainty with respect to the quantity and sources of available sugar, and these producers say they are forced to move production outside the United States.

In some years, despite the requirement that the government operate the sugar program at no cost, government outlays have reached as high as US$259 million in a given year. Some analysts suggest the program could operate at no cost if restrictions remain in place with Mexico, but the Congressional Budget Office issued a report in 2016 projecting US$138 million in government outlays over the next ten years for the sugar program. At a minimum, the average American is financially supporting sugar production in a way that is unique among agriculture commodities. The cost goes unnoticed on a day-to-day basis, but an analysis conducted at Iowa State University estimates the US sugar program decreases consumer welfare by as much as US$2.9 to US$3.5 billion each year.

Support for the program

Sugar farmers, refiners, processors and others associated with sugar production argue that, without the government’s management of supply from overseas, they would be effectively put out of business. Why? Because the cost of producing sugar in the United States is typically higher than in lower cost countries such as Brazil. American producers argue that part of the reason their competitors can charge less is because foreign governments subsidize production, reducing the cost of production for their own farmers. US production is likely to be down this year, while production in countries including Brazil, Thailand, China, Pakistan, Russia, and members of the European Union is increasing, putting more pressure on the US market to take excess world sugar in respond to consumer demand.

A timely debate

The US Congress is reauthorizing the “farm bill” in 2018. The discussions will determine the shape of the US sugar program for the next four years. In late December 2017, a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced The Sugar Policy Modernization Act, which would give the US Department of Agriculture more flexibility in how import quotas are administered.

As we have pointed out in other TradeVistas articles, the debate over trade-limiting policies often pits one set of producers against another — in this case, some 18,000 sugar crop farmers and processors versus some 600,000 Americans employed in making food products that use sugar.

Did Hostess move Twinkie production to Mexico due to the relatively high cost of sugar in the United States under the sugar program? We don’t know. We do know that it’s an urban legend that Twinkie’s can survive a nuclear war or last 45 years (the shelf life is 45 days). The question is, will the current version of the US sugar program last 45 years?

For more detail read: U.S. Sugar Program Fundamentals, Congressional Research Service, April 2016

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).