Published 27 April 2018

In Ferris Bueller's Day Off, Bueller's classmates stare blankly, blow bubbles, and fall asleep on their desks as high school teacher Ben Stein (an economist in real life) explains how the United States sank deeper into depression in the early 1930s. As he drones on, asking the students questions – “Anyone? Anyone?" – few of the movie's fans realize he's teaching one of the most important lessons in the history of trade policy: how Congress muffed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

What’s wrong with raising tariffs? Anyone? Anyone?

Most Americans – even younger Millennials – have seen the 1986 classic, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. While Bueller is skipping school, his classmates stare blankly, blow bubbles, and fall asleep on their desks as high school teacher Ben Stein (an economist in real life) explains how the United States sank deeper into depression in the early 1930s. As he drones on, asking the students questions — “Anyone? Anyone?” — few of the movie’s fans realize he’s teaching one of the most important lessons in the history of trade policy: how Congress muffed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

The lesson is timely for three reasons. First, in the annals of Congressional history, Smoot-Hawley is cited as an egregious instance of “log-rolling” – members blatantly traded votes to protect each other’s constituents behind tariff walls. Second, increases in tariffs significantly reduced trade as part of the American economy. Third, the negative experience and impact of Smoot-Hawley led Congress to delegate trade negotiating authority to the executive branch as a pressure valve against protectionist demands. All three outcomes laid the foundation for a re-orientation toward free trade, the institutional structures in the US government to pursue it, and an American commitment to lead tariff reductions globally.

The founders of the American tariff

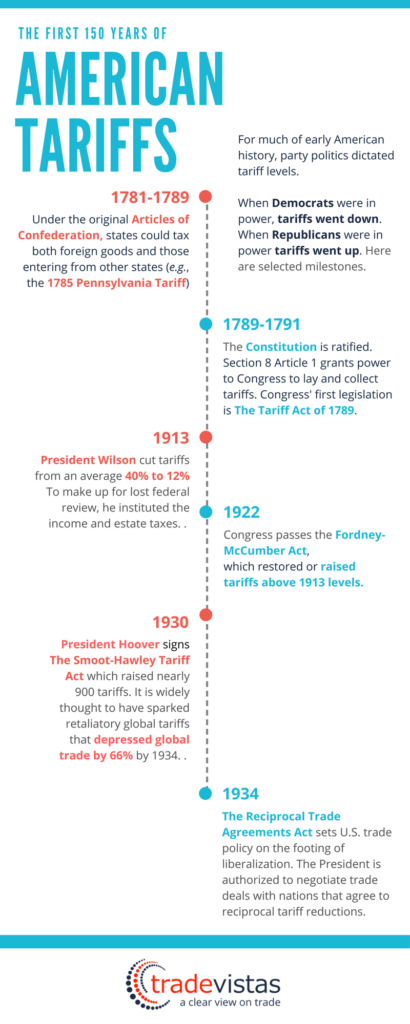

For a time after the American Revolution, before the United States Constitution went into effect, the American states imposed their own duties on foreign goods and on goods moving among the states. States with ports along the East Coast, from Massachusetts to Georgia, levied different tariffs on British goods and fees on British vessels. Without a coordinated tariff code, British traders avoided the highest duties by engaging in arbitrage, entering their goods through the cheapest ports.

The experience helped convince states to grant Congress the power to impose and collect import duties and to regulate commerce with foreign nations. Dispensing in the first seven sections of the Constitution with the particulars of how Congress will operate, import duties are addressed in the first sentence of Section 8 as the first order of business for the Congress:

SECTION. 8.

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises…but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States

Congress moved swiftly to exercise this power. The Tariff Act of 1789 was the first major Act passed in the United States. It stated two purposes: first, to generate revenue to support the new federal government, enabling the Congress to also pay down debts incurred during the Revolution; and second, to “encourage and protect” the manufacturing of goods in the United States.

The debate over the impacts of high tariffs on the fledgling American economy mirrors some of the debate we’re having today. Agricultural-producing states viewed high duties as primarily benefiting manufacturing states, to which James Madison responded that the rest of the nation would inevitably “shoulder a disproportionate share of the financial burden.” Alexander Hamilton warned that setting high tariff too high would be tantamount to economic warfare with Great Britain, which would cause trade to decline and instead reduce revenues needed to run the government and finance the national debt.

A yo-yo diet of political tariffs

Economist and trade historian, Doug Irwin, summarizes the 50 years of trade policy leading up to Smoot-Hawley this way. “From the 1880s through the 1930s, the politics of the tariff issue appeared quite simple: when the Republicans were in power they would raise the tariff, and when the Democrats were in power they would lower the tariff.”

Yo-yoing tariff rates hit an important low and high in 1913 and 1922, respectively. President Wilson saw tariffs as protection for fat cat producers and a tax on the poor. Having instituted new income and estate taxes in 1913 to make up for lost revenue, Wilson cut tariffs from an average 40 percent to 12 percent. By 1922, as wartime markets receded and European production began to recover, President Harding worked with Congress on a tariff law, the Fordney-McCumber Act, that restored or raised tariffs above 1913 levels, and authorized the president to raise or lower a given tariff by 50 percent to even out differences in foreign and domestic production costs.

The tariffs had a deleterious effect on European trading partners recovering from the First World War. Failing to convince the Americans to lower rates, European countries raised their own tariffs. As a percentage of the American economy, trade fell by half. It would foretell the impact of Smoot-Hawley in 1930, a preview that went unheeded.

The last general tariff law passed by Congress was a whopper

In the second half of the 1920s, President Herbert Hoover was sympathetic to the plight of American farmers, whose prices were falling in part due to global overproduction. He sought to protect them with tariffs, but once Congress began the business of handing out tariff increases, a line of special interests formed out the door.

More than 1,000 businesses, trade associations, lobbyists, farmers, unionists testified before Congress over 45 days of hearings that produced some 11,000 pages of testimony. Congressional procedures at the time enabled roll-call votes on tariffs for specific goods. Members horse-traded votes to protect industries concentrated in their districts, knowing that the costs would be spread among all Americans.

Tariffs reduce trade

In all, nearly 900 tariffs were increased. In many cases the tariffs were applied as specific amounts per volume imported, not as a percentage of the import value. So while prices for basic goods dropped due to deflation, tariffs kept the cost of imports prohibitively high.

Did Smoot-Hawley help turn the stock market crash and recession into the Great Depression? Economists and scholars disagree about the protective effect of the tariffs, the impact they had in worsening the Great Depression or preventing recovery, and whether they were the cause of retaliatory tariffs imposed by more than a dozen other countries including Canada, Britain, Germany, and France.

The volume of American imports had already dropped by 15 percent the year before Smoot-Hawley. By two years after Smoot-Hawley, imports fell another 40 percent. In 1929, the United States exported US$5.24 billion worth of goods. By 1933, exports dropped to US$1.68 billion. Whether the goal was to merely stifle imports, what is not disputed is that world trade declined overall by 66 percent between 1929 and 1934, and that American exports suffered as well, removing an important source of recovery and growth.

One of the most defining events in US economic history

Smoot-Hawley was a watershed moment that fundamentally shaped modern American trade policy. Four years after Smoot-Hawley, Congress enacted a very different sort of trade law – the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 – which authorized the President to negotiate and implement trade deals with other nations that agreed to reciprocal tariff cuts.

Tariffs have unintended consequences. Special interest requests cannot be accommodated without impact to rest of the economy. One request leads to others. Congress realized it might need to restrain its own powers by sharing trade-making authority with the executive branch, which is thought to be more immune to lobbying by special interests.

The movie ends the same way

I was recently asked, “What’s wrong with tariffs?” It was a thoughtful question from a farmer in the Midwest regarding recent announcements by the Trump Administration about possible tariff hikes. Many trade practitioners have ingrained the lessons of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 and remain wary of the slippery slope created when particular sectors of the economy are singled out for protection behind tariff walls.

The dangers of raising tariffs have been proven in history. The lessons of Smoot-Hawley serve as a reminder to tread cautiously when wielding tariffs as a trade policy tool. We’ve seen this movie before.

Share this graphic:

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).