Protectionism

Who’s Really Paying for the Wall?

Published 02 February 2017

If Trump is serious about applying a 20 percent tariff on Mexican imports to pay for the wall construction, it’s the US that will pay. And the bill could come in as much as 900% above cost.

If the Trump Administration is serious about applying a 20 percent tariff on goods from Mexico to pay for new construction on a wall along the United States and Mexico, it’s the United States that will pay, not Mexico. And the bill could come in as much as 900% above cost.

Raising Money with a Tariff

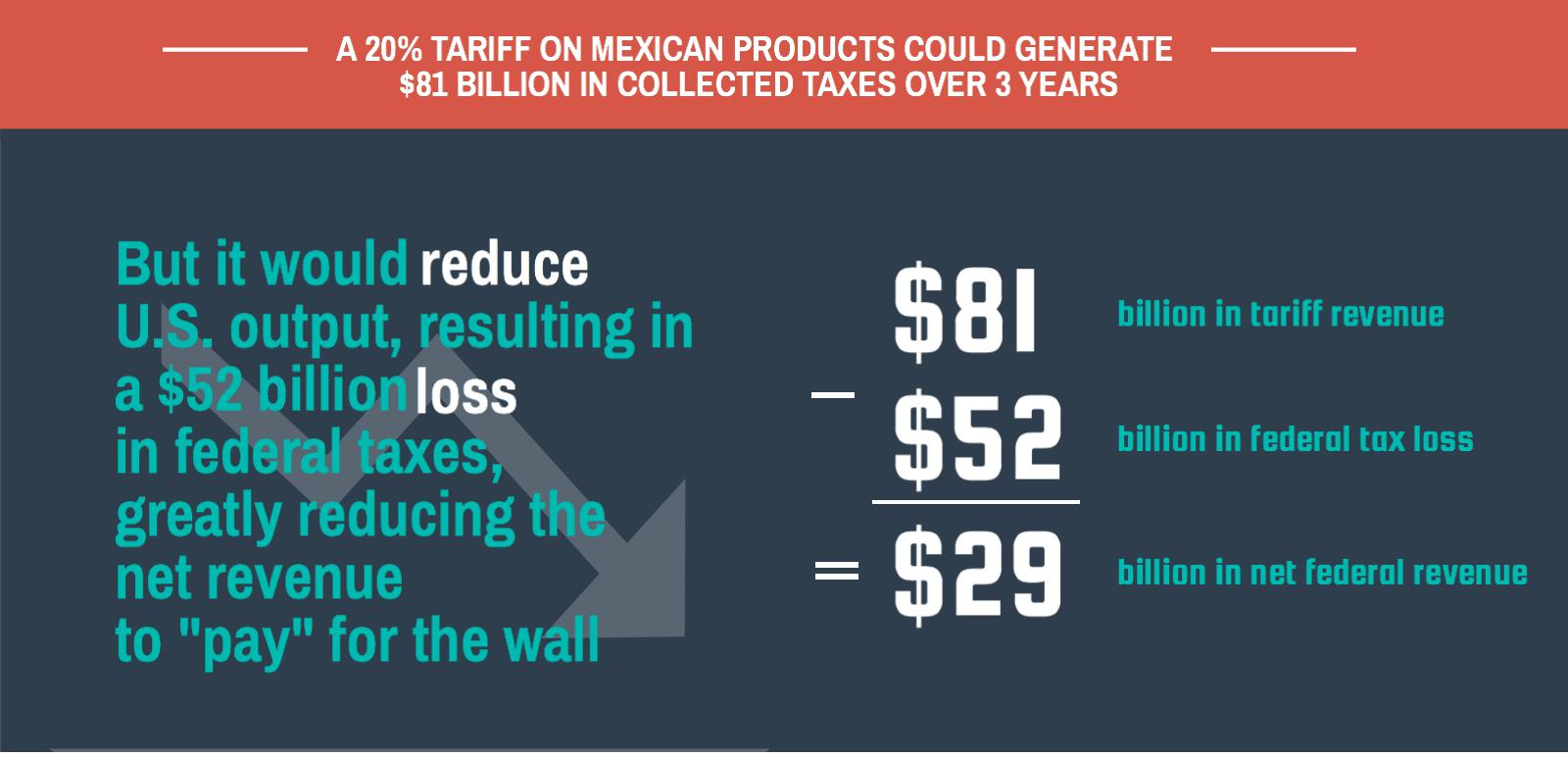

Bernstein Research puts the cost of the wall at between $15 and $25 billion. We calculate, using a widely accepted model of international trade, that the 20 percent tariff on U.S. imports from Mexico would need to remain in effect for as long as three years to raise enough money to “pay” for the wall. Here’s why.

American Winners and Losers

Putting a new tariff on imports would potentially raise $26.9 billion a year, but it would also induce ripple effects through the U.S. economy. Some American companies and workers would gain an advantage as the prices of competing products from Mexico go up. They could increase their U.S. output and hire more people, boosting U.S. GDP.

But companies and workers that use inputs from Mexico to make goods in the United States would see their input costs rise, and many would be forced to raise the prices of their finished goods. The price paid by American families at the register for everyday goods like avocados, or for common big ticket necessities like cars, would also rise. Charging customers more would put sales at risk, which could eventually force firms to lay off workers. These impacts would reduce U.S. GDP.

What’s Left in the Fed’s Pocket

Lower output means lower federal tax revenues, which would drop by an estimated $17 billion a year, offsetting much of potential revenue from the import tariffs. After all is said and done, the U.S. Treasury would net $9.7 billion a year to spend on the wall – or about $30 billion over three years.

The Wall’s Unexpected Costs

But federal tax revenues are a small part of the story. Lower output resulting from the 20 percent tariff on imports from Mexico would wipe out about $95 billion, or 0.5 percent, from GDP annually. Over three years, the bill comes to $286 billion in lost value to the U.S. economy and a loss of 755,000 American jobs. Two-thirds of those job losses would be at the expense of low- to medium-skilled workers.

In addition, mayors and governors would have to deal with the fallout from $25 billion in lost state and local revenues over those three years. The new Administration would also find itself paying out unemployment benefits to a host of newly out-of-work Americans, a cost not included in these estimates.

And we haven’t even factored in the potential effects if Mexico were to retaliate against U.S. exports to Mexico, which Mexico would be entitled under trade rules to do.

So who really pays for the wall? American manufacturers, consumers, and workers. And, we’d be charged 900% more than it costs to build. Not a very good deal, by any measure.

Explanation of Methodology:

Our estimates are derived from a 100-region, 23-sector structural general equilibrium mode combined with econometric foundations based on recent structural gravity models. The model is an Eaton-Kortum type model. The database is from GTAPv9, updated to available 2015 data. It captures all the up- and downstream impacts, the gains and the losses, that result from imposing a tariff on U.S. imports from Mexico.

In this scenario, companies view the tariff as temporary, so capital is not moved to other sectors or regions of the world. In addition, workers do not have time to react to the changed economic environment by moving to new jobs or accepting lowering the wages.

Click here to share this infographic:

Authors:

By Dr. Joseph Francois, Managing Partner at Trade Partnership Worldwide, LLC (Washington, DC) and Managing Director at the World Trade Institute (Bern), and Laura M. Baughman, President, Trade Partnership Worldwide, LLC.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).