Protectionism

Both Sides of the Manufacturing Equation

Published 10 February 2017

Helping one set of manufacturing workers can put others in harm's way. Like, anti-dumping duties on primary metals might help 400,000 workers, but it disadvantages 6 million other workers.

President Trump and his economic team have an opportunity to fix something that none of their predecessors have been able to get right.

Price Discrimination

In the Essential on the brewing battle over China’s market economy status, TradeVistas offers a simplified explanation of “dumping” in international trade. A form of price discrimination, dumping is said to occur when foreign manufacturers sell their goods at a lower price than they charge their domestic consumers.

Under U.S. anti-dumping laws, a finding of dumping enables the imposition of a tariff on the goods being dumped. The tariff is meant to basically make up the difference created by discrimination by increasing the price of the imported product. That can provide temporary relief for the company or companies competing with lower-priced imports, but it raises costs for U.S. companies and industries that depend on those same lower-priced imports.

Down in the Dumps

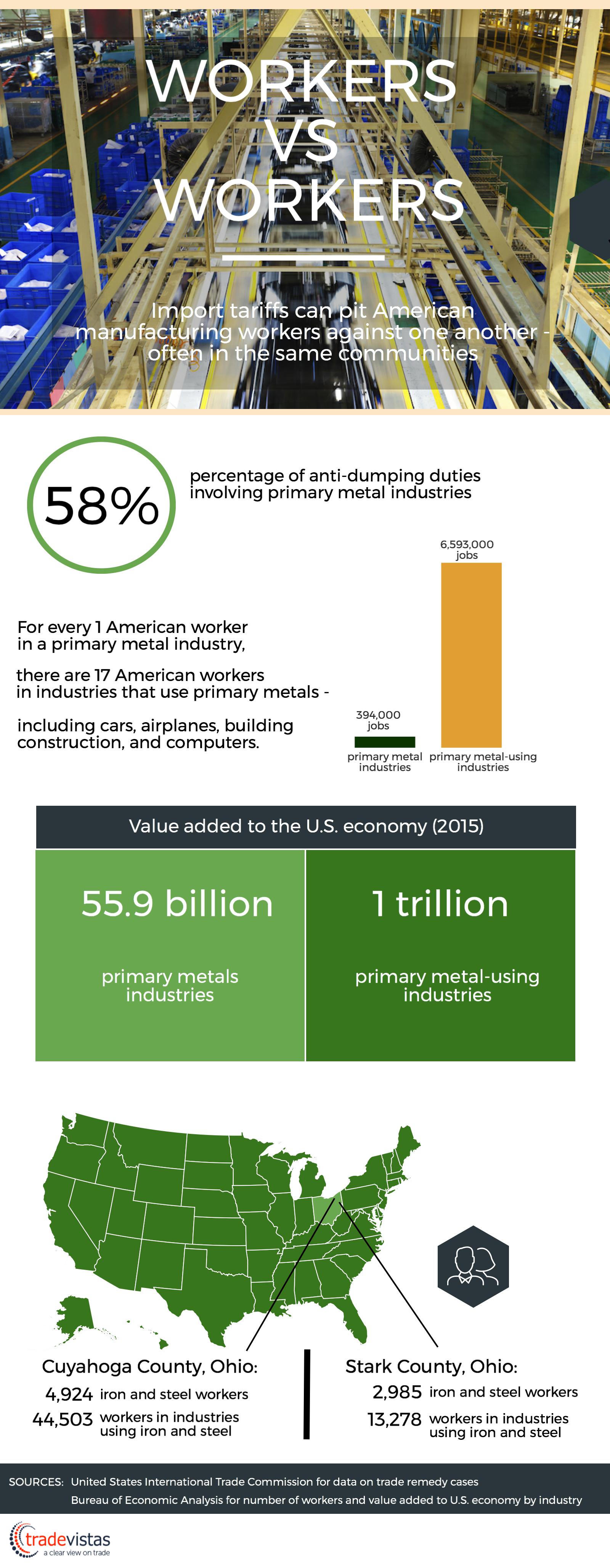

Fifty-eight percent of anti-dumping duties are awarded in cases involving primary metal industries. U.S. producers in these industries have been hard hit over the last decade by excess production in China that is subsidized in some form by the Chinese government. In an effort to alleviate losses, these industries have sought protection from “unfair” competition. At the same time, many U.S. manufacturers rely on iron, steel, and other metals to make their products. The anti-dumping duties means they have to pay more for those materials than what their competitors are paying on the world market, which puts them at a disadvantage.

One for Every 17

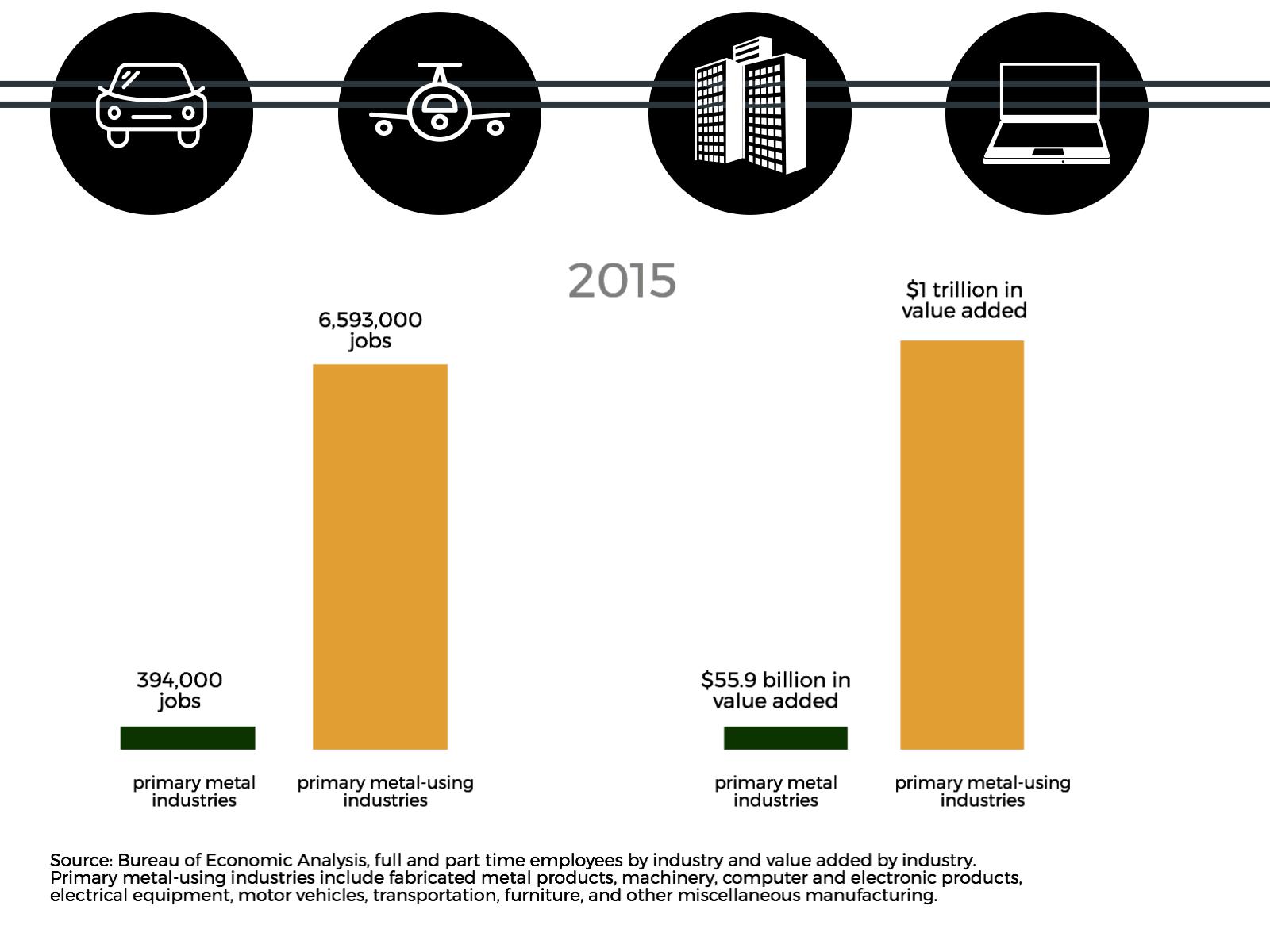

In 2015, 394,000 Americans worked in primary metal industries that include steel, aluminum, copper and others, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In comparison, over 6.5 million Americans are employed in industries that rely on those metals as inputs, such as machinery, computers, electrical equipment, motor vehicles, and other fabricated metal products.

Neighbor v. Neighbor

These workers live in the same communities. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, is home to 4,924 iron and steel workers. The county is also home to 44,503 workers in manufacturing sectors that use these metals as inputs. Stark County is home to 2,985 iron and steel workers, and 13,278 downstream manufacturing workers.

It isn’t just a matter of jobs. Consider also the value created by different industries. Primary metal manufacturing added $55.9 billion in value to the U.S. economy in 2015. Manufacturers that use primary metals as direct product inputs created $1 trillion in value to the U.S. economy.

Sophie’s Choice

The price impact is clear on downstream (consuming) industries of anti-dumping duties on products used in production processes. The effects of a less competitive upstream market, and possible supply shortages resulting from the investigation itself and cessation of imports after the duty is imposed, can also cause harm to downstream users. A 1999 economic study calculated the collective net economic welfare cost of anti-dumping duties at that time to be $4 billion, or .06% of GDP. In today’s terms, that translates into $10.8 billion.

What about jobs? Does the anti-dumping duty save more jobs than it costs? Empirical evidence suggests that anti-dumping duties cost more jobs in downstream production than jobs saved in upstream production dig deeper with these studies. But because the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) doesn’t typically study the employment impact, the data for actual cases is somewhat sparse.

In 1995, the USITC did estimate the economic effects of an anti-dumping duty on tapered roller bearings*. The effects of dumping alone: a net loss of 27 jobs. The effect of the anti-dumping duty: a net loss of 169 jobs. The duty cost more jobs than it saved.

The True Cost of an Import Tariff

Before President Trump intervened to secure tax breaks to stay in Indiana, executives at Carrier, an American air conditioning manufacturer, cited high costs as a factor in their decision to move production.

“Relocating our operations to a region where we have existing infrastructure and a strong supplier base will allow us to operate more cost effectively so that we can continue to produce high-quality HVAC products that are competitively positioned while continuing to meet customer needs.”

– Chris Nelson, President of HVAC Systems and Services North America, Carrier

Consider the example of Carrier’s Performance Series MAQB12B1, 12,000 BTU Single Zone High Wall Mini Split retails for approximately $1,600 per unit. Air conditioners are generally made of different types of metal, many of which are subject to antidumping and countervailing duties:

Steel (64% to 191% duty)

Copper (25% to 27% duty),

Aluminum (8% to 374% duty)

The precise cost share of metals in this air conditioner is not publicly available. But metals are 15 percent of the input cost of machinery on average. To the extent these inputs are imported, these duties could mean an additional $19 to $898 per unit in supply costs alone.

Workers in Harm’s Way

Anti-dumping duties on primary metals might help 400,000 metal workers, but it also disadvantages 6 million other manufacturing workers, whose families and communities equally value their jobs.

The USITC determines whether a petitioning industry has experienced injury from imports for the purpose of imposing anti-dumping duties, but does not have to analyze the harm to companies, industries, and the U.S. economy from imposing those duties. Yet helping one set of workers with anti-dumping duties can put other workers at risk.

Taking the step to include the impacts to downstream industries and their workers in USITC analyses would begin to assure that both sides of the manufacturing equation are considered.

*U.S. International Trade Commission (1995), The economic effects of antidumping and countervailing duty orders and suspension agreements, Washington, DC, see Table 14-17

The views in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent Sidley Austin, LLP, or any of the firm’s clients.

SHARE THE FULL INFOGRAPHIC:

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).