Protectionism

We are in a Trade War — With Ourselves

Published 09 March 2018

The few domestic companies that may (or may not) benefit from special treatment shouldn’t outweigh the costs for the rest of the economy.

A trade war in the headlines

The Trump administration’s recent decision to impose new tariffs (border taxes) on selected products stirred up talk of a trade war. The announcements in January this year of border taxes reaching 20 percent to 50 percent on imported washing machines, and 30 percent on imported solar panels, is cause for alarm. Even Chinese business titan Jack Ma is scared.

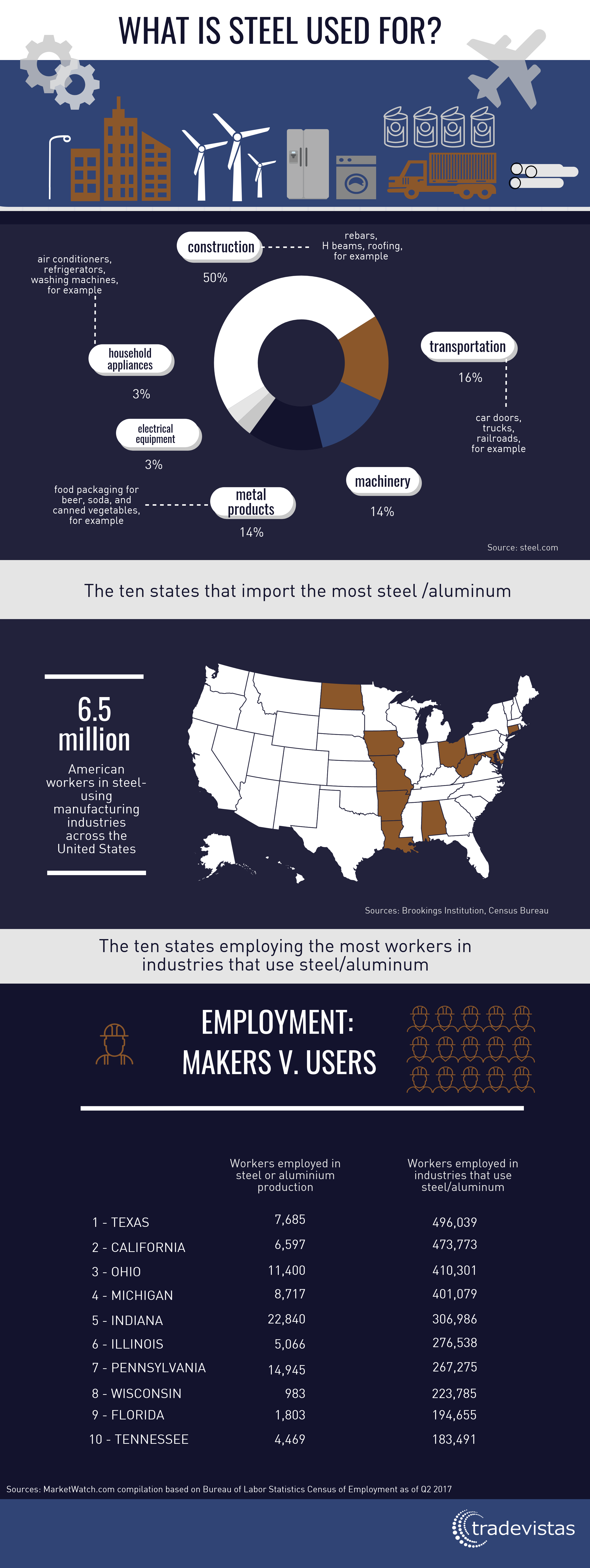

Now the administration is weighing a decision on whether to apply a 25 percent tax on imported steel and a 10 percent tax on imported aluminum. The taxes are being considered as a means to counteract the effects of low-priced commodities undercutting U.S. producers, which stems from subsidized overproduction in places like China. But the new tax would hit U.S. suppliers from Canada the hardest (China is actually our 11th largest supplier) and could backfire on the U.S. economy.

It is a trade war, but not with China — with ourselves.

There’s not a lot of disagreement about the nature of the root problem. The disagreement we’re having in the United States right now is over the response.

President Trump wants Americans to be prosperous. He sees imports surging and American firms hurting. On the surface, using a border tax to raise the price of imports relative to domestic goods seems like a nudge in the right direction to help domestic firms.

He is not alone. Nearly everyone who has occupied the Oval Office has succumbed to the desire to protect American firms from competition abroad. Meanwhile, workers in industries later in the production process, firms and consumers have suffered the force of these taxes.

For instance, the Solar Energy Industries Association stated that the 30 percent tariffs on solar panels would cancel billions of dollars in investment, weaken demand, and eliminate 23,000 installation jobs in America. Worse still, solar panel installer is the fastest growing occupation across America. Requiring only a high school diploma or equivalent and on-the-job training, these jobs are sorely needed for much of our workforce. Meanwhile, the domestic firm that the tariff is meant to help employs just 300 people.

In this way, border taxes for select products end up pitting special interests against Americans. Consumers and importers pay a higher price, and there is less healthy competition to satisfy consumers’ needs in the marketplace.

A few American business versus many American businesses

By their very nature, so-called “trade remedy” laws were designed to protect the interests of a few domestic producers at the expense of hundreds of thousands of other domestic firms, workers and consumers. These laws were written several decades ago when trade was a small share of the economy, and what we traded was mostly agriculture and final goods.

Today, exports and imports are 11.9 percent and 14.7 percent of the U.S. economy, more than double what they were 50 years ago. And a big part of that trade is in intermediate goods, which are in-between raw materials and final goods. More than 40 percent of U.S. imports are intermediates.

U.S. firms rely on access to the best inputs at the best prices to stay competitive.

U.S. firms increasingly rely on access to the best inputs at the best prices to stay competitive. According to OECD data, the overall foreign value added share of US exports is imports is 15 percent, up from 11.4 percent in 1995.imports contribute 15.3 percent of the value of U.S. exports. Two of our most competitive industries — advanced manufacturing and energy — are among the most reliant on imports.

Like it or not, this is what firms have to do to stay competitive.

Rich or poor, few households want the government dictating prices in the marketplace. Worse still, this government meddling causes more harm than good. The few domestic companies that may (or may not) benefit from special treatment shouldn’t outweigh the costs for the rest of the economy.

It may be time to update our trade laws

The desire to promote U.S. economic growth and a better quality of life for all Americans is nearly universal across policymakers. But our current “trade remedy” laws have unintended consequences for the American businesses they are not meant to protect.

Congress appears to be reasserting itself in trade policymaking. A record number of congressional staff went to Montreal for the latest NAFTA gathering, Congress is demanding more frequent and comprehensive trade policy updates, and the president will need congressional renewal of his Trade Promotion Authority if he is to make any new deals. The question of how to modernize outdated trade laws are worth their attention.

As a first step, Congress could require a full consideration of the effects of border taxes on all American firms, workers, and consumers before such measures are taken. By putting their interests on equal footing with those of special interests, we can eliminate this war with ourselves.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).