Published 18 August 2017

After autos and auto parts, energy commodities are the largest category of traded goods in North America. The energy industry in North America is both highly integrated and interdependent. As a region, we have achieved energy self-sufficiency and have become a global energy powerhouse because we trade with one another.

The Road to U.S. Energy Independence Runs North and South

After autos and auto parts, energy commodities are the largest category of traded goods in North America. The energy industry in North America is both highly integrated and interdependent. As a region, we have achieved energy self-sufficiency and have become a global energy powerhouse because we trade with one another.

NAFTA eliminated tariffs for crude oil, gasoline, and certain refined products used in energy-intensive manufacturing, improving the affordability of energy products for consumers in all three countries. Under the U.S. Natural Gas Act, U.S. natural gas producers are permitted to export to Canada and Mexico by virtue of having a free trade agreement in place. As a result of liberalized trade, our markets are able to offer reliable, efficient, and flexible sources to meet one another’s energy requirements.

What Does “Interdependence” Look Like?

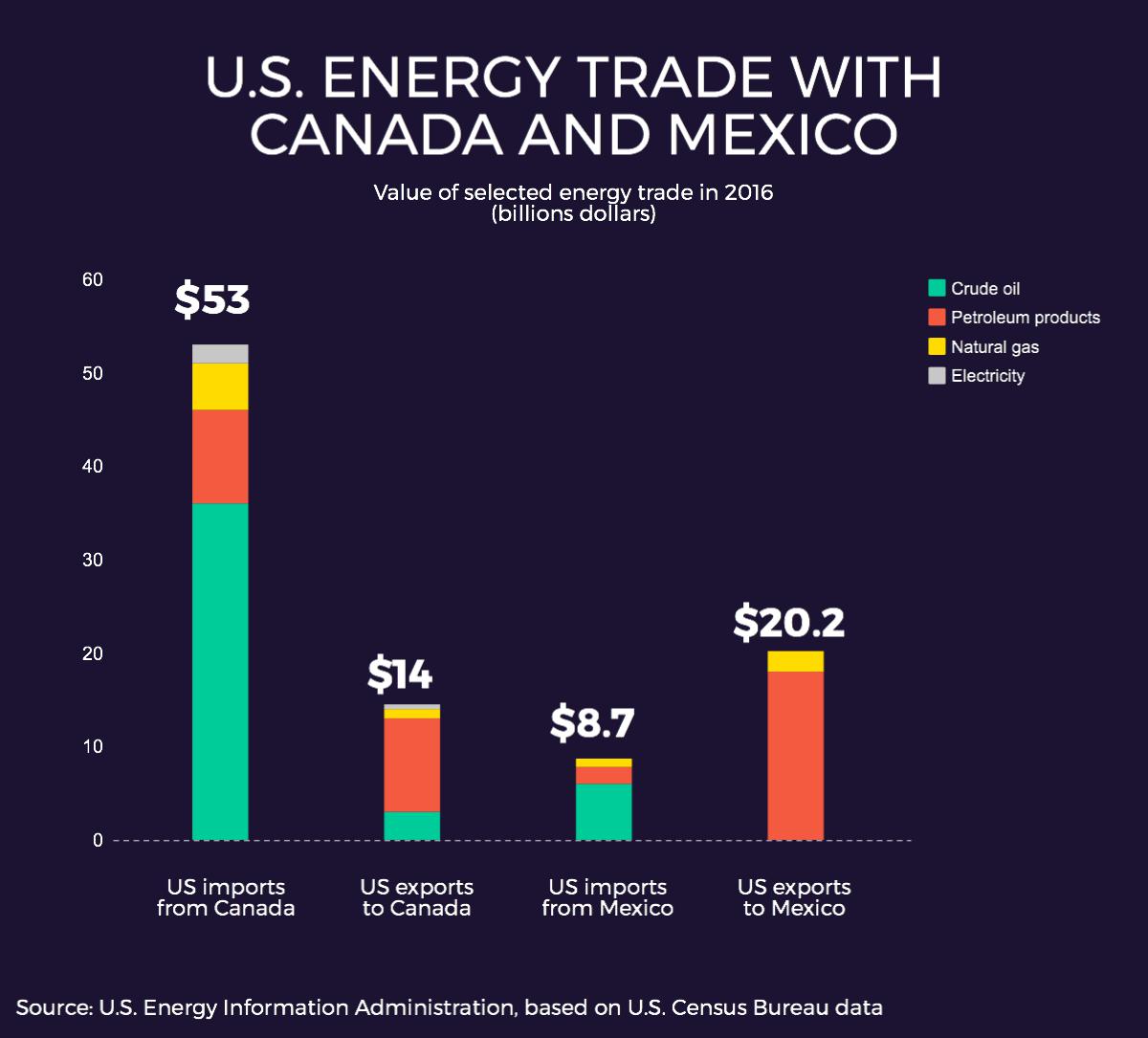

Crude Oil: The largest segments of North American energy trade are crude oil, petroleum products, and natural gas, with electricity a distant fourth. Canada’s reserves of crude oil are estimated at 173 billion barrels, compared with reserves in the United States and Mexico of around 35 billion and 10 billion barrels respectively. Owing to its vast resources, Canada is the largest foreign supplier of crude oil to the United States, and the United States is Canada’s main customer (having been its only foreign customer for many years).

Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling that enabled shale production in North Dakota, Texas and Montana have reduced the volume of U.S. imports from Canada. Imports from Mexico have also declined as that country’s oil production has declined, but the United States is Mexico’s largest customer, receiving most of Mexico’s crude oil exports. Overall, the United States relied on its NAFTA partners for nearly half of its crude oil imports in 2016; by expanding energy trade in North America, the United States was able to reduce its dependence on less reliable suppliers elsewhere in the world.

Petroleum Products: U.S. refineries are configured to process heavy crude oils from Canada and Mexico. Mexico and Canada in turn are major buyers of the petroleum products refined mainly in the U.S. Midwest and Gulf regions. Over the last decade, U.S. exports of petroleum products to Canada have increased around 300 percent, bringing petroleum product imports and exports with Canada close to parity. U.S. imports of petroleum products from Mexico have declined around 40 percent over the last decade, while U.S. exports to Mexico of petroleum products increased around 170 percent, making the United States a net exporter of petroleum products to Mexico.

Natural Gas: The United States produces about 90 percent of the natural gas consumed domestically, relying on Canada as a cost effective and flexible source to fill U.S. demand. In 2016, the United States supplied around 90 percent of Mexico’s daily imports, the equivalent of about 30 percent of Mexico’s daily demand for natural gas. Demand in Mexico for U.S. natural gas, including liquefied natural gas, is expected to nearly double in the next three years as Mexico invests to increase its capacity to produce natural gas-fired electricity. U.S. pipeline capacity is expanding rapidly to accommodate increased natural gas flows between the two countries.

NAFTA Could Support Deeper Integration

In general, Mexico’s historic reforms to open its energy sector to foreign participation is viewed by the U.S. energy industry as a very positive step that will create new opportunities to further integrate the North American energy market. The U.S.-Mexico Energy Business Council has put forward a number of recommendations to facilitate increased trade and investment in the energy sector. Among them, the industry would like for regulators to collaborate with industry to increase regulatory alignment among the three countries, for example by harmonizing safety and emergency response standards both on and offshore.

The industry in all three countries recommends streamlining U.S. permitting processes, and see NAFTA as a critical and timely opportunity to support Mexico’s energy reforms including best practices for licensing and bidding. The U.S. industry is interested as well to ensure investor protections as the Mexican energy market opens to more foreign investment; they see the protections in an upgraded NAFTA as helping to de-risk their investments and improve confidence in the sanctity of contracts in Mexico. Further, while Mexican reforms opened investment opportunities to foreign firms, U.S. operators would benefit from a NAFTA-based market access obligation in energy services. Many in the industry also cite a pending shortage of highly skilled experts, professionals, and technicians in Mexico. Being able to temporarily assign internal talent to support Mexico’s burgeoning energy sector is highly desirable for U.S. industry and would help support the building of a stronger talent pipeline in Mexico over the long run.

Energy Leadership Founded on Regional Strength

Last week, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported in its Short-Term Energy Outlook that 2017 is the year the United States will become a net exporter of natural gas. With the shale revolution, the United States now produces more natural gas than is consumed domestically, creating the opportunity to export excess production.

Demand for all fuel types is expected to rise 48 percent globally by 2040. Today, developing countries that are not members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) account for 57 percent of total world energy consumption. Their usage is predicted to increase by 70 percent by 2040, compared with an increase of 18 percent in developed OECD countries. China and India alone account for more than half of increased demand over this period.

What’s driving the growth in demand is a combination of increased industrial output globally (50 percent of energy consumption) and rising standards of living and personal income particularly in developing countries, leading to growth in transportation energy to move people and freight as well as increased use of energy in commercial and residential buildings. U.S. shipments create greater certainty in global supply and put downward pressure on global, market-based prices.

After lifting crude oil export restrictions in December 2015, the United States also expanded the number and variety of foreign customers for U.S. crude oil, exporting to 16 different nations in 2016. The security of North American supply and ability to move resources and energy products throughout the region without undue restrictions is the solid foundation for the United States’ new-found flexibility to export its production.

Deficit Revisited

Because petroleum products account from between 10 to 17 percent of total trade in the region, energy trade significantly affects the U.S. trade balance with its NAFTA partners. As commodities, the price of energy and energy products fluctuates, affecting the value of the trade balance. If you’re counting the trade balance (and we’ve suggested you shouldn’t), the U.S. trade deficit with its NAFTA partners is generally smaller if energy goods are excluded. In some years, the United States runs a surplus in non-energy goods.

Given that, perhaps Canada and Mexico will ask for their own “re-balancing” if the United States persists with its current trade deficit obsession. As described above, given the importance of energy trade and investment flows within North America, there are bigger national and economic security implications to consider than deficit accounting.

Sources: Data cited in the section on interdependence are derived from the excellent data products on the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) website at eia.gov

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).