Published 24 March 2017

WTO commitments do not prevent countries from negotiating agreements but they are considered exceptions. Here’s what you need to know about agreements designed to create free-trade areas.

Around the world, hundreds of free trade agreements are in force or under negotiation. WTO commitments do not prevent countries from negotiating these separate agreements, but they are considered exceptions and must meet certain criteria. Here’s what you need to know about agreements designed to create free-trade areas.

What’s in a Name?

In common parlance, we use the term free trade agreement or FTA, but the WTO agreements refer to these agreements as “regional trade agreements” or RTAs.

Why are they called regional trade agreements? Because early efforts to integrate economically were among countries in the same region, like the North American Free Trade Agreement among the US, Canada, and Mexico, the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement among countries in Southeast Asia, and MERCOSUR, the Southern Common Market Agreement involving the countries of South America.

Today, RTAs are the vehicle to negotiate free-trade areas that are not strictly regional. Trade agreements are driven less by geographic proximity than by a host of other considerations including the trade and investment patterns that developed through global supply chains. The European Union calls their agreements Economic Partnership Agreements. India and MERCOSUR call their agreement a Preferential Trade Agreement. In the WTO, these are all RTAs.

Are RTAs the Exception or the Rule?

In practice, they are becoming commonplace and have been proliferating over the last decade. Under WTO rules, they are the exception.

In another Essential, we described the principle and obligation of non-discrimination as the foundation of the global trading system. Although there are benefits to economic integration and trade liberalization outside the WTO, it’s important to acknowledge that, by definition, RTAs discriminate by offering more favorable treatment to its parties than what’s offered to WTO members.

In effect, trade agreements create new patterns of trade, but they do this by diverting trade that might otherwise develop or grow absent the agreement. That makes them inconsistent with WTO obligations. The WTO therefore treats them as exceptions and provides conditions for those exceptions.

Three Essential Conditions

WTO agreements reflect members’ desire to strike a balance between enabling members to pursue economic integration while avoiding “to the greatest extent possible…creating adverse effects on the trade of other Members.”

The specific conditions for regional trade exceptions can be found in Article 24 and the Enabling Clause of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1994) and Article 5 of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Broadly, to constitute a legitimate exception to WTO obligations, RTAs must meet three conditions:

(1) The agreement should cover “substantially all trade” among the parties to the agreement. (You should not select just a few products or services where you’ll eliminate duties just for each other.)

(2) The agreement should not raise barriers to trade with countries that are not party to the agreement. (The agreement might have the effect of diverting trade, but you should not specifically create new barriers in the agreement.)

(3) The agreement should result in a free trade area within a “reasonable length of time.” (Though not defined, ten years is considered reasonable for achieving the elimination of duties on all non-agricultural goods. Often longer periods of time are granted for agricultural commodities and a handful of very sensitive traded goods.)

Everyone’s Doing It

In June 2016, Mongolia notified the WTO of its RTA with Japan, making it official that all WTO members now have at least one RTA in force.

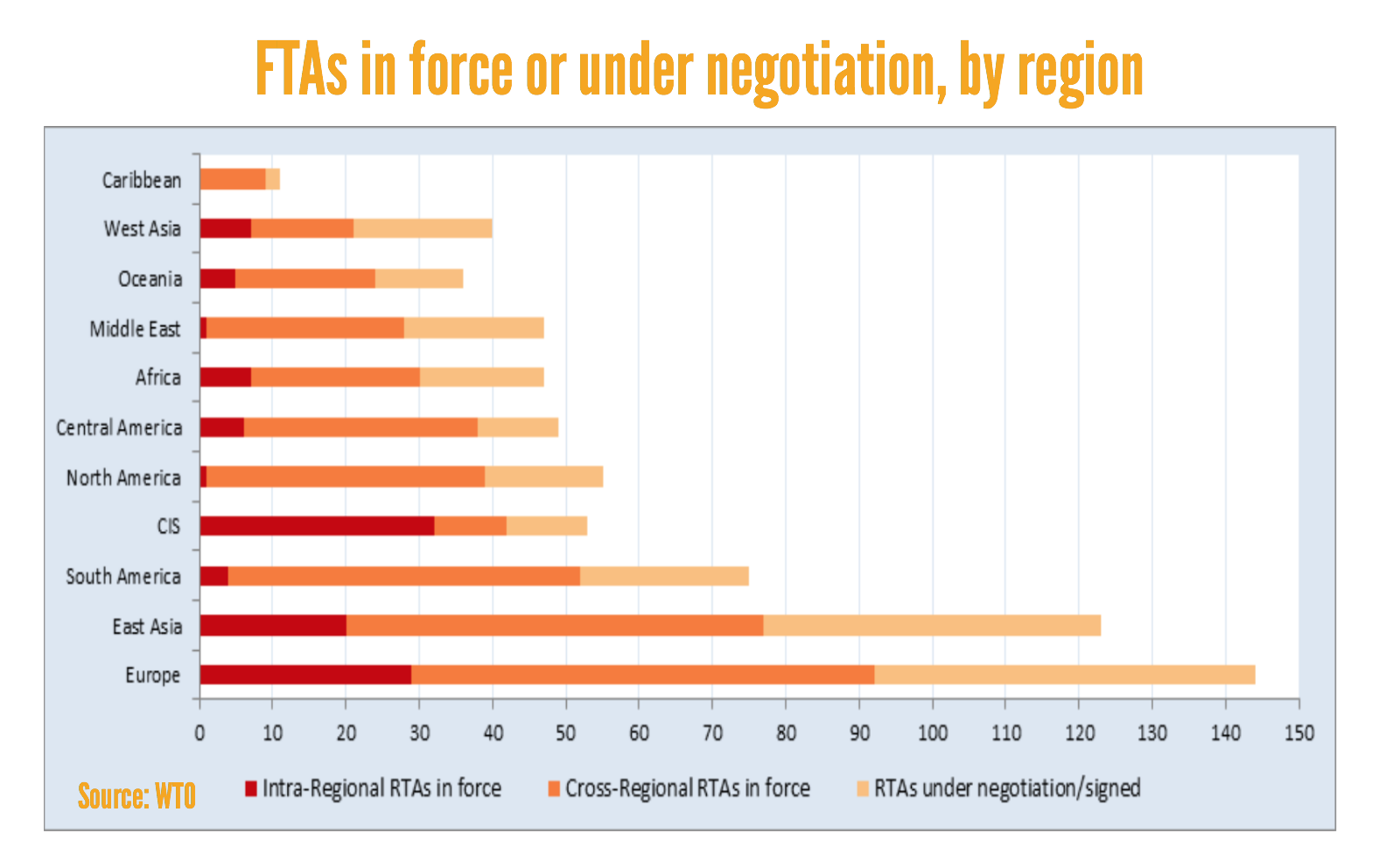

WTO members are supposed to notify their agreements to the WTO secretariat, which maintains a public database. According to the WTO, 124 agreements were notified between 1948 and 1994. Since 1995, members have notified over 400 additional agreements. WTO members can report their agreements under the goods agreement and the services agreement, so there’s some double counting in that number — there are actually around 270 “physical” agreements in total. The United States is a party to just 14 of those. The European Union has negotiated 38 agreements.

To Negotiate, or Not to Negotiate

Governments have decisions to make about whether to pursue free trade agreements and which countries to negotiate with. They base these choices on factors that include national economic strategy, geopolitical relationships, perhaps a dash of free trade philosophy, and sometimes, national security considerations.

For many years, while other countries set about stitching together a network of trade agreements, the United States held steadfast to a philosophy of using the World Trade Organization as the vehicle for global liberalization. In the 2000s, the Bush Administration launched a strategy to create a “competition in liberalization,” which encompassed negotiating on all fronts – bilaterally, regionally, and multilaterally through the WTO.

Advancing Global Trade or Carving it Up?

It’s no coincidence that many countries doubled down on a strategy of negotiating RTAs when multilateral negotiations got bogged down in the WTO. In recent years, some significant “mega-deals” have been contemplated and negotiated. They include the Transpacific Partnership agreement among 12 countries (now 11 since the United States withdrew after the deal was concluded), the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the United States and Europe, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which would integrate the members of ASEAN with India, China, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, and Australia.

Regionalism can lead to a patchwork of agreements with different rules and preferential arrangements. Navigating those differences can raise the transaction costs for business. But when liberalization slows or fails to advance through the WTO, regional agreements can become stepping stones toward global agreement and incubators for new and more advanced provisions covering aspects of the modern economy not yet contemplated in WTO agreements. The parties to these agreements reap benefits, but many developing and least developed countries are not parties to many RTAs, so if RTAs become the main path to trade creation, some countries could be left behind. We’ll explore this debate in future Features and Essentials.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).