Digital trade

Static Trade Laws are Careening Toward Obsolescence

Published 14 July 2017

In an era when who trades, what is traded, and how it's trade are in constant flux, the only constant for international trade rules is the potential for obsolescence. Technological innovations are testing the limitations - and rationale - of the old rules.

Light Years Ahead

The private sector is constantly coming up with new ways of doing things. On a good day, government regulation struggles to keep up. Consider that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was created in 1934 to regulate interstate commerce in radio signals.

In an era when who trades, what is traded, and how it’s trade are in constant flux, the only constant for international trade rules is the potential for obsolescence. Technological innovations are testing the limitations — and rationale — of the old rules.

Take the example of 3D printing, also known as Additive Manufacturing. 3D printing is a production method in which material is added layer by layer in a controlled fashion to build up a component. It’s the reverse of “subtractive” techniques like milling and stamping (where material is removed from a larger piece to make the finished item). 3D printing permits a high degree of customization, and can produce parts without the time-consuming and expensive step of creating tooling.

Under Section 337 of the Trade Act of 1930, the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) can issue an order to exclude articles from entering the United States that have been found to violate U.S. intellectual property rights. Because the administrative procedure often take less time than a lawsuit, and because enforcement is usually fast and effective, Section 337 has been a popular tool for fast-paced and innovative industries to combat theft of their intellectual property.

“Scotty, beam me up”

Section 337 seemed to work well until a new product came along that didn’t seem to fit the standard definition of “an article”. Here’s the case in short form.

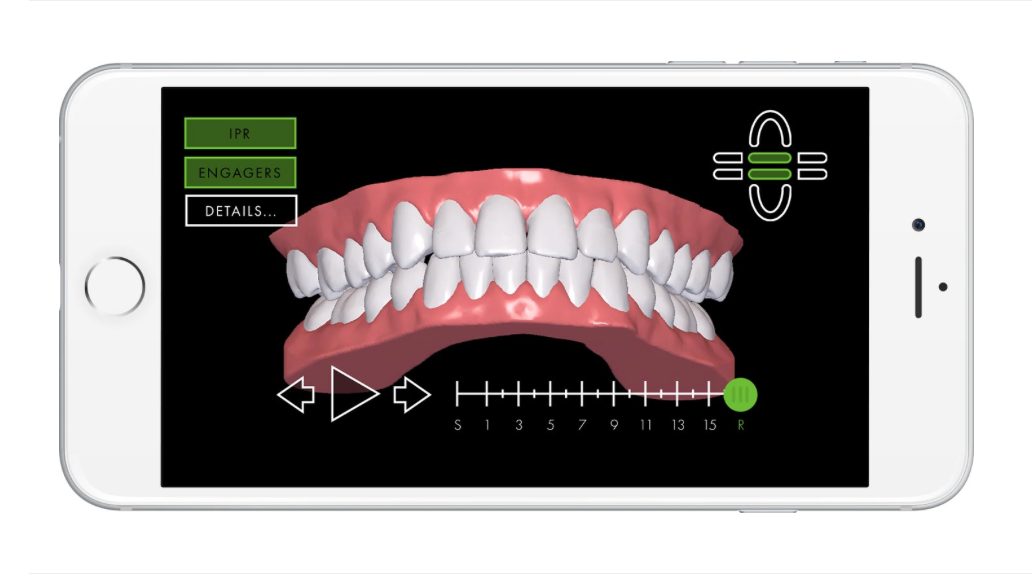

ClearCorrect is a Texas company with operations in Pakistan. They use 3D printing technology to produce teeth aligners. An American dentist can make a physical model of a patient’s teeth and then scan it to create a 3D digital file. This file is transmitted to Pakistan, where workers determine the final tooth placement and generate a set of sequential aligners. That product is also in the form of digital files, which ClearCorrect then transmits back to the American dentist, who uses a 3D printer in his or her office to produce the aligners for the patient’s use.

ClearCorrect was accused of infringing on seven different patents. The USITC issued an order requiring American dentists to cease downloading the files and selling the 3D-printed aligners (USITC Inv. No. 337-TA-833). ClearCorrect appealed the ITC’s decision, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reversed the ITC’s decision (ClearCorrect v. ITC, 2014-1527).

Why the reversal? The court’s opinion held that Section 337 provides jurisdiction over “articles that infringe,” with articles interpreted to mean material things — not digital transmissions. Since the machine that made the aligners was located in the U.S. dentist’s office, the only thing imported was the digital instructions (the 3D blueprints).

Image: clearcorrect.com

Weightless Trade Matters

The court’s 2015 decision generated a debate including among those in the entertainment and software industries. Limiting the ITC’s jurisdiction to “material things” makes it more difficult for leading-edge firms to protect intellectual property for what we now consider the cross-border supply of digital services. These services — inventions — have value, even if they don’t have weight.

What happens next? Section 337 was created in 1930 and last amended in 1988, several years before the commercial use of the Internet. It’s always possible for Congress to amend the statute to cover “weightless” goods.

The fact that there is a disconnect should not be surprising. Back in 1998, Diane Coyle published “The Weightless World,” in which she foresaw the need to address the implications for politics, business, and careers when important portions of our life have literally no weight. This court decision is one more wake-up call: not only does weightless trade matter, trade laws will have to evolve to reflect the dynamic nature of global commerce.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).