Published 21 February 2019

As digital trade expands, so have barriers like data localization. How are trade agreements around the world adjusting to this digital shift?

Search, click, buy – it’s all data

E-commerce allows us to order anything around the world with just an Internet connection and the click of a button. Whether we’re streaming music from Sweden’s Spotify, downloading a video game designed in Africa, or paying a design freelancer in Bangladesh, global digital trade has quickly become a part of our everyday lives. Yet, international trade rules are still racing to catch up with an increasingly digitally connected world.

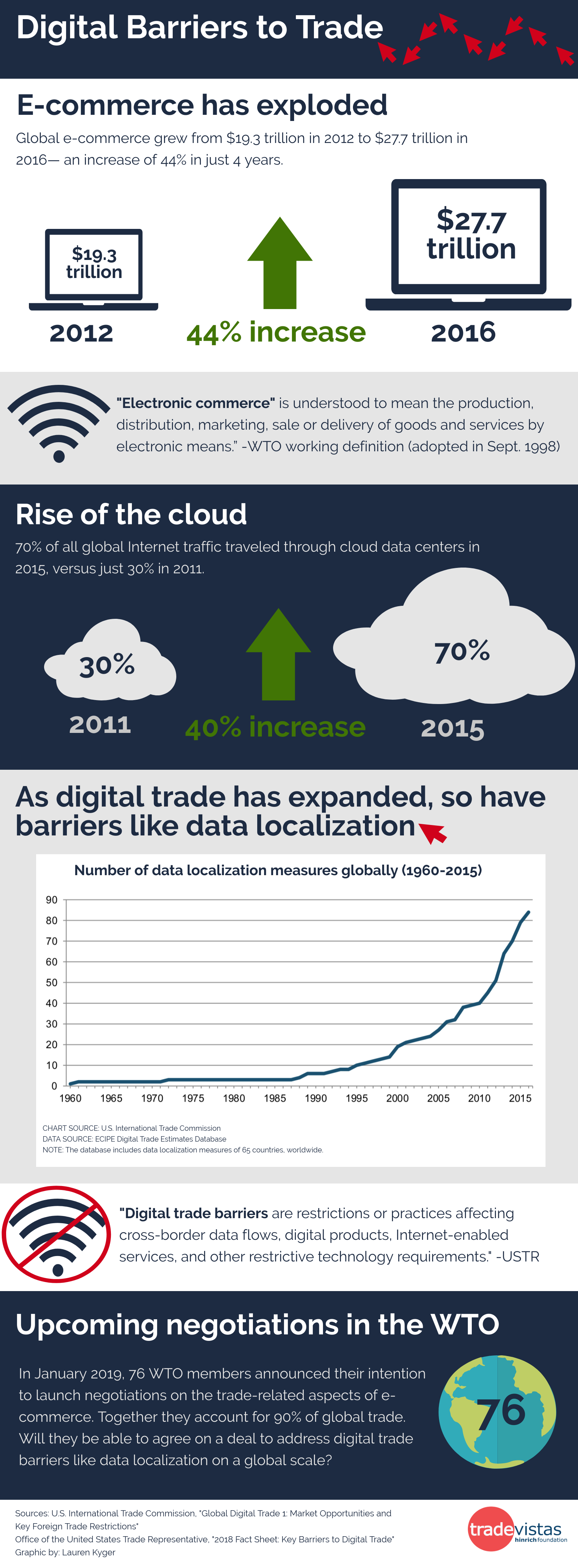

Global e-commerce, or the sale of goods of services over the Internet, has grown from US$19.3 trillion in 2012 to US$27.7 trillion in 2016— an increase of 44 percent in just four years. In addition to customers buying online, businesses are increasingly utilizing digital networks to make their products, manage global value chains, and provide services to customers.

Every search, click and purchase we make online is “data”. Although we can’t physically see our data flows, they are pivotal in facilitating global trade. Companies are using cloud computing for smart manufacturing, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, among other cutting-edge technologies. According to the U.S. International Trade Commission, 70 percent of all global Internet traffic traveled through cloud data centers in 2015, versus just 30 percent in 2011.

The United States wants data to flow freely across borders to better facilitate global digital trade. Other countries, like China and Vietnam, have passed laws to try and control the flow of data in the name of privacy and cybersecurity. What’s missing are international trade rules that address growing barriers to digital trade on a global scale.

What is data localization?

Digital trade barriers are defined by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) as restrictions or practices affecting cross-border data flows, digital products, Internet-enabled services, and other restrictive technology requirements. Data localization policies fall within this category, as do web filtering and blocking, customs tariffs on digital products, requirements to disclose source code, and more.

Data localization laws often require foreign companies to store data on local servers. More broadly, data localization includes all policies that impede the transfer of data like making companies process data locally or requiring individual or government permission before transferring data. These types of policies restrict the flow of data, and up the cost for foreign companies to compete in local markets by forcing them to spend more for additional IT, data storage and other duplicative services.

The number of data localization measures has doubled in the last six years, according to a 2017 report by the U.S. International Trade Commission. The same report said that data localization was most cited by US industry representatives as the policy measure impeding digital trade.

Mapping key barriers to digital trade

In its annual National Trade Estimates of Foreign Trade Barriers report, USTR lists countries where data localization measures are in play. Unsurprisingly, China and its “Great Firewall” top the list. China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law and 2015 National Security Law prohibit or restrict cross-border transfers and impose data localization requirements on companies in “critical information infrastructure sectors”. Other countries with data localization measures include Indonesia, Nigeria, Russia, Turkey and Vietnam.

The European Union also applies restrictions on cross-border data flows. In May 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into force, limiting the data transferred between countries based on specific privacy frameworks.

Time for trade rules to think digitally

In response to the growing digital nature of trade and the proliferation of digital trade barriers, there has been a recent flurry to include digital trade chapters in recent free trade agreements, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). These agreements protect the free flow of information across borders, while prohibiting data localization, mandatory disclosure of source code, and customs duties on digital products.

What’s still missing is a multilateral agreement from the World Trade Organization on digital trade. WTO members have long agreed to not impose customs duties on electronic transmissions. While digital trade is encompassed in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), specific digital issues such as data localization and forced technology transfer are not addressed.

There has been recent movement from WTO members to negotiate on these modern topics. In January, 76 WTO members— including the US, EU and China— announced their intention to launch negotiations on the trade-related aspects of e-commerce. If able to successfully negotiate and draw a conclusion, the group— which together account for 90 percent of global trade— could help streamline efforts to address digital trade barriers like data localization on a global scale.

Share the graphic:

Recommended reading:

Cross-Border Data Flows: Where Are the Barriers, and What Do They Cost? by Nigel Cory of the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, May 2017

United States International Trade Commission Report, “Global Digital Trade: Market Opportunities and Key Foreign Trade Restrictions”

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and Conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).